Go for the Pole

We left off yesterday with two princes of polar aviation—Richard E. Byrd and George Hubert Wilkins—squaring off in Antarctica. The prize, yet again, was the Pole.

These men had practical motivations, too. Byrd wanted to show that the airplane could handle polar conditions—and he wanted the U.S. Navy to upstage the rival flying corps in the Army (there would be no distinct Air Force for another two decades).

Wilkins, meanwhile, had lived through a devastating drought on his family’s farm, and hoped to establish meteorological observing stations in both polar regions, to improve weather forecasting for farmers.

Both sought to extend the reach of human technology into the polar regions. But each wanted to do it first. Technology didn’t care about any symbolic first…humans, however, did.

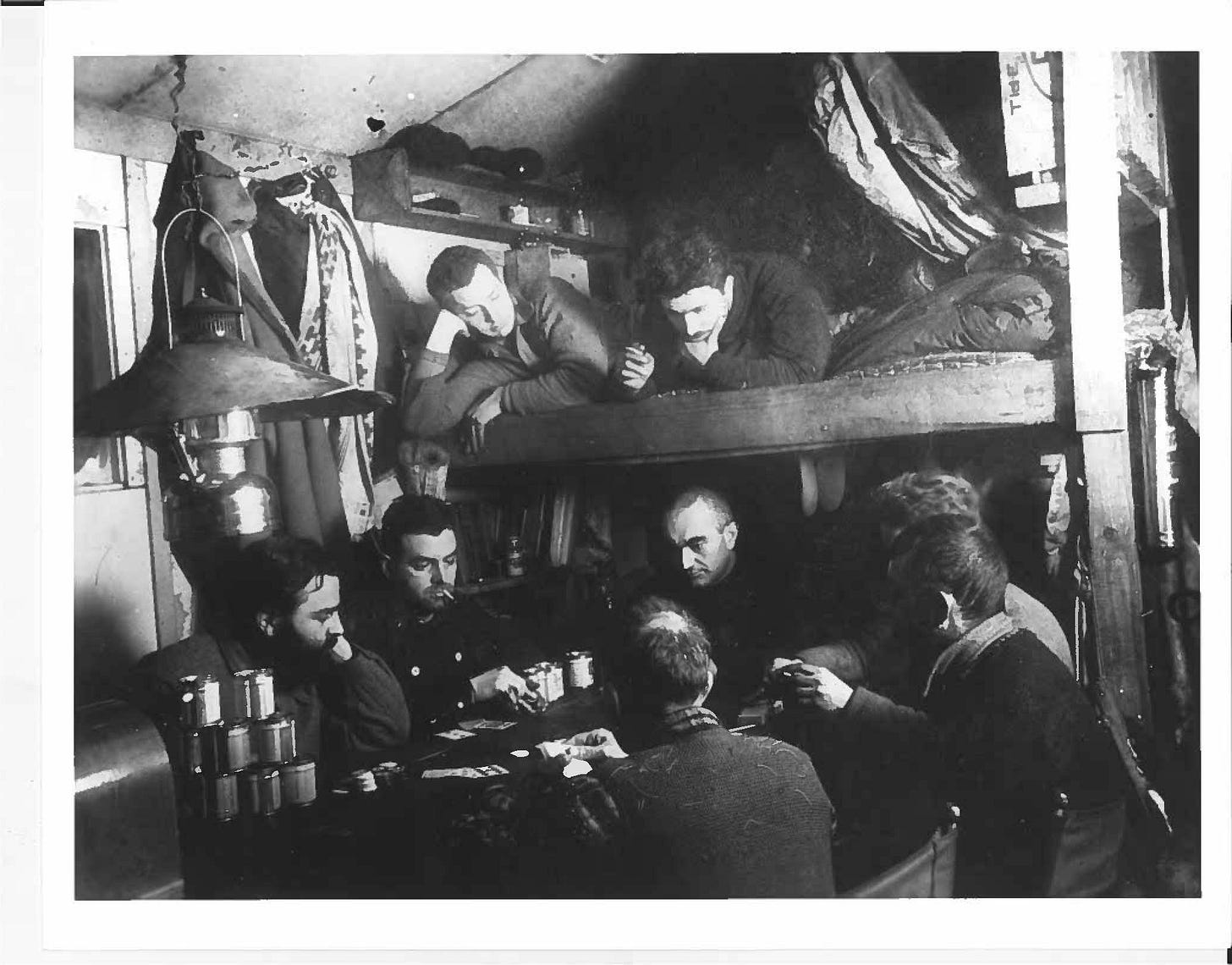

And so, on Monday, July 15, 1929, as Byrd’s men wintering in Little America listened to their regular broadcast of personal radio messages from friends and family, they got a surprise.

One of the dog sled drivers, 25-year-old Jacob “Jack” Bursey, records the transmission in his diary:

Weather fine

Temp 43° below zero

Wonderful moonlight night

Lost one of my pups […]

Message concerning Wilkins

Lecture from June on aviation motors

What did Bursey think of Wilkins’s announcement? He doesn’t say. Some of his later entries, though, offer clues.

What’s the opposite of a Byrd’s eye view?

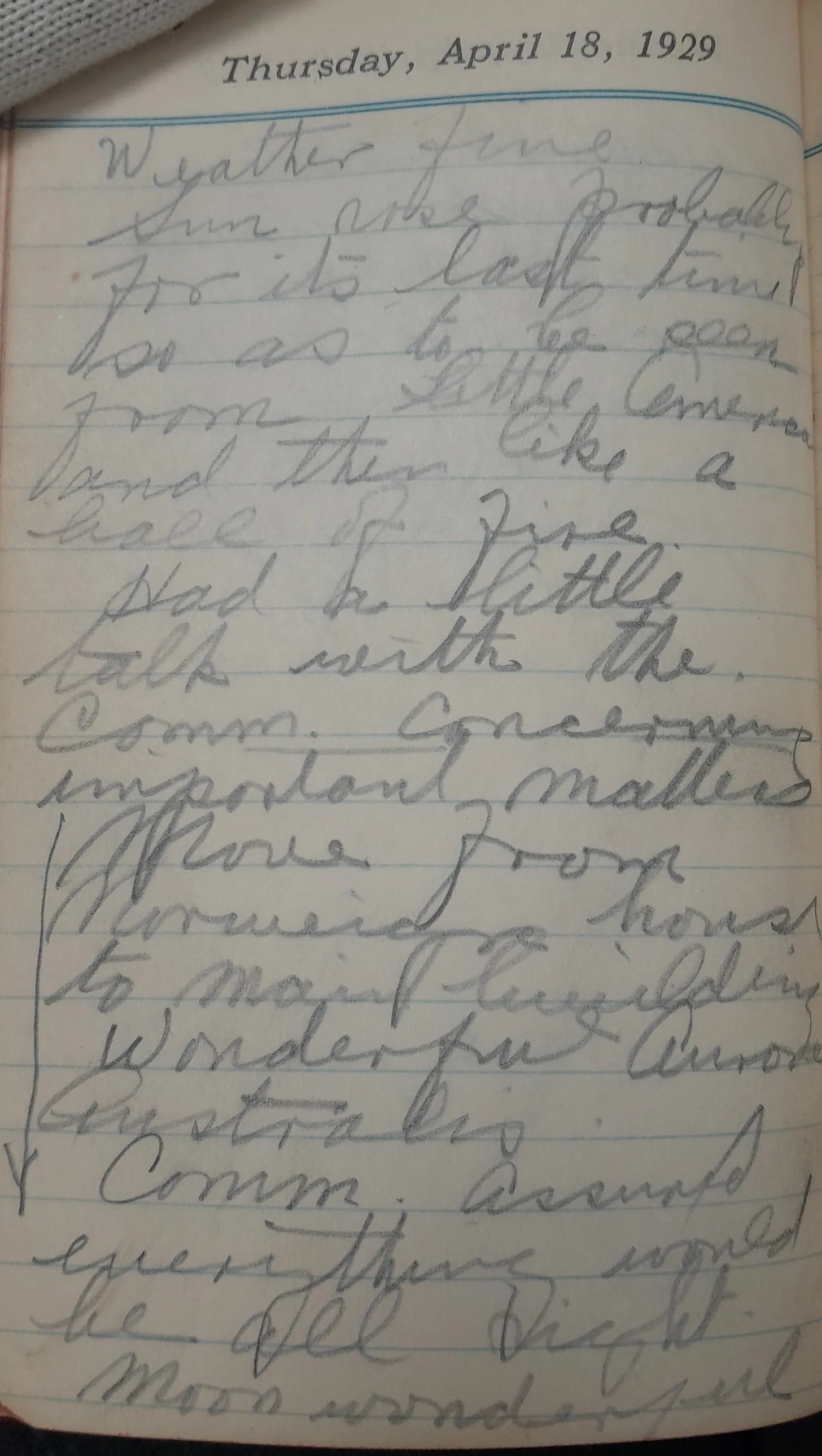

From his diary, Bursey seems to be a hard worker, with an occasionally sly sense of humor (one practical joke involved a pig), and a great admiration for “Commander Byrd.” A few months earlier, Bursey had had a talk with the Commander about “important matters.” Bursey doesn’t explain, but ends by saying: “Comm. assured everything would be all right. Moon wonderful.”

Bursey’s spare, understated style can’t hide his excitement about their mission. On January 24, he writes:

“Weather snowing. Fell through the ice with a load of coal and had to call for help from ship. The Fairchild plane made a flight to test radio on short waves and broke the world’s record by getting San Francisco and New York Times.”

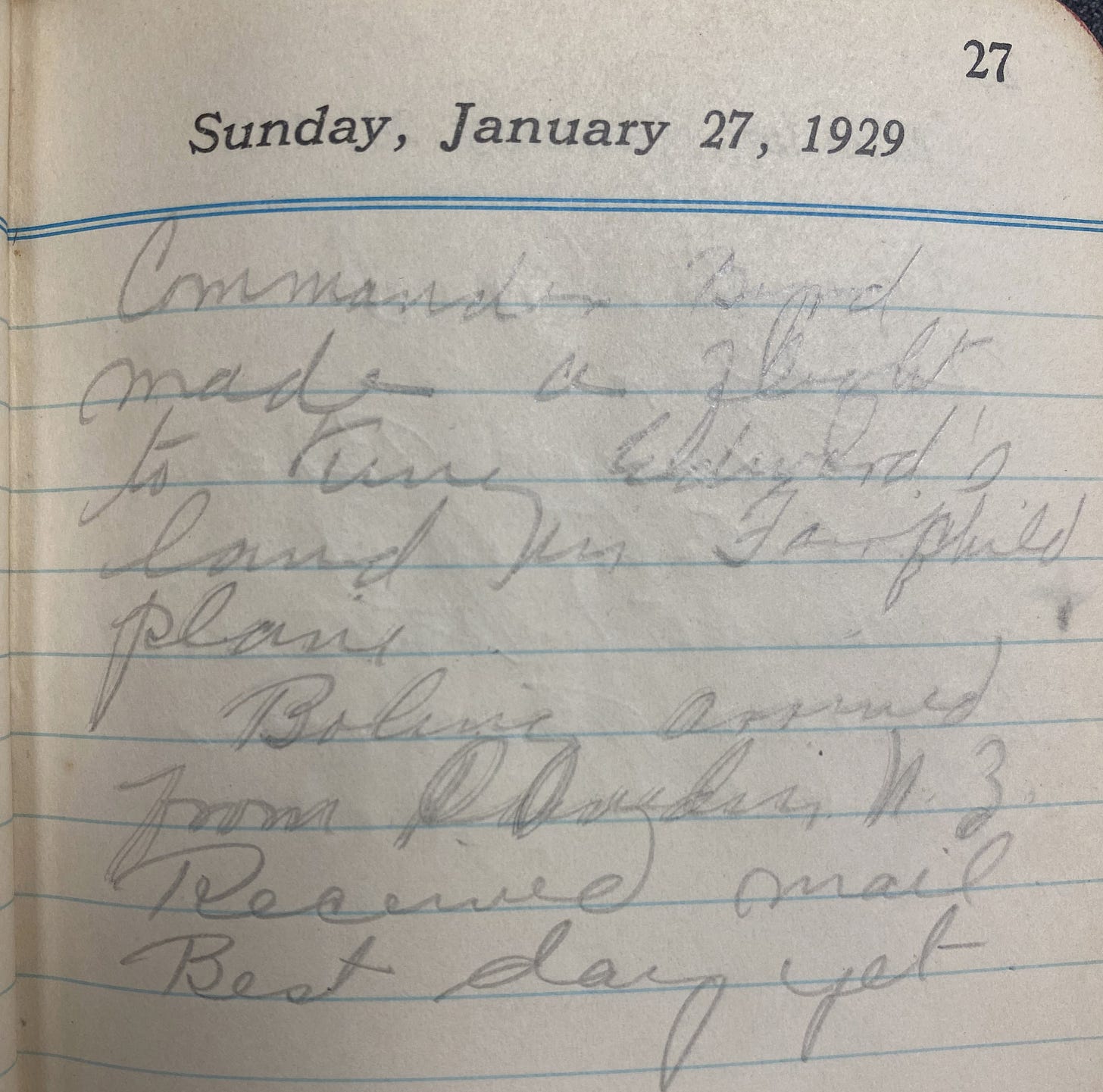

Three days later, he’s more openly thrilled:

“Commander Byrd made a flight to King Edward’s land in Fairchild plane […] Received mail

Best day yet”

Then on February 5 he records: “Snowmobil started working today. First snowmobil to run over the Barrier.”

On April 25, it’s: “Temp 58 below zero a record at this time.” (Apsley Cherry-Garrard saw 77 degrees below in 1911, but that was the dead of winter.)

Bursey even records his—the?—first Antarctic ice cream on May 21: “Ice cream for supper the first in the Antarctic.” That same day, he also “Spoke to Commdr. concerning world record in dog driving.”

In selecting Bursey to winter over in 1929, Byrd was signaling his trust in the young dog team driver. Bursey, for his part, seemed to reciprocate by spending more time in the library and taking navigation lessons. He made his time count.

With summer came trouble. On November 19, Little America got another transmission: Wilkins was back at Deception Island with his beloved Lockheed Vegas, the planes he’d flown over both polar regions. For Byrd, it was do or die.

Byrd told his men: “Don’t forget that Wilkins is out to beat us.”1

Bursey makes only one mention of Wilkins, but it’s not likely he had forgotten. His life on the ice had been filled with firsts—including his first polar flight on the expedition’s Fairchild, which took the men up for sightseeing tours. They’d marked the anniversary of Byrd’s North Pole flight on May 9th with a “Big celebration.”

Only one big first remained.

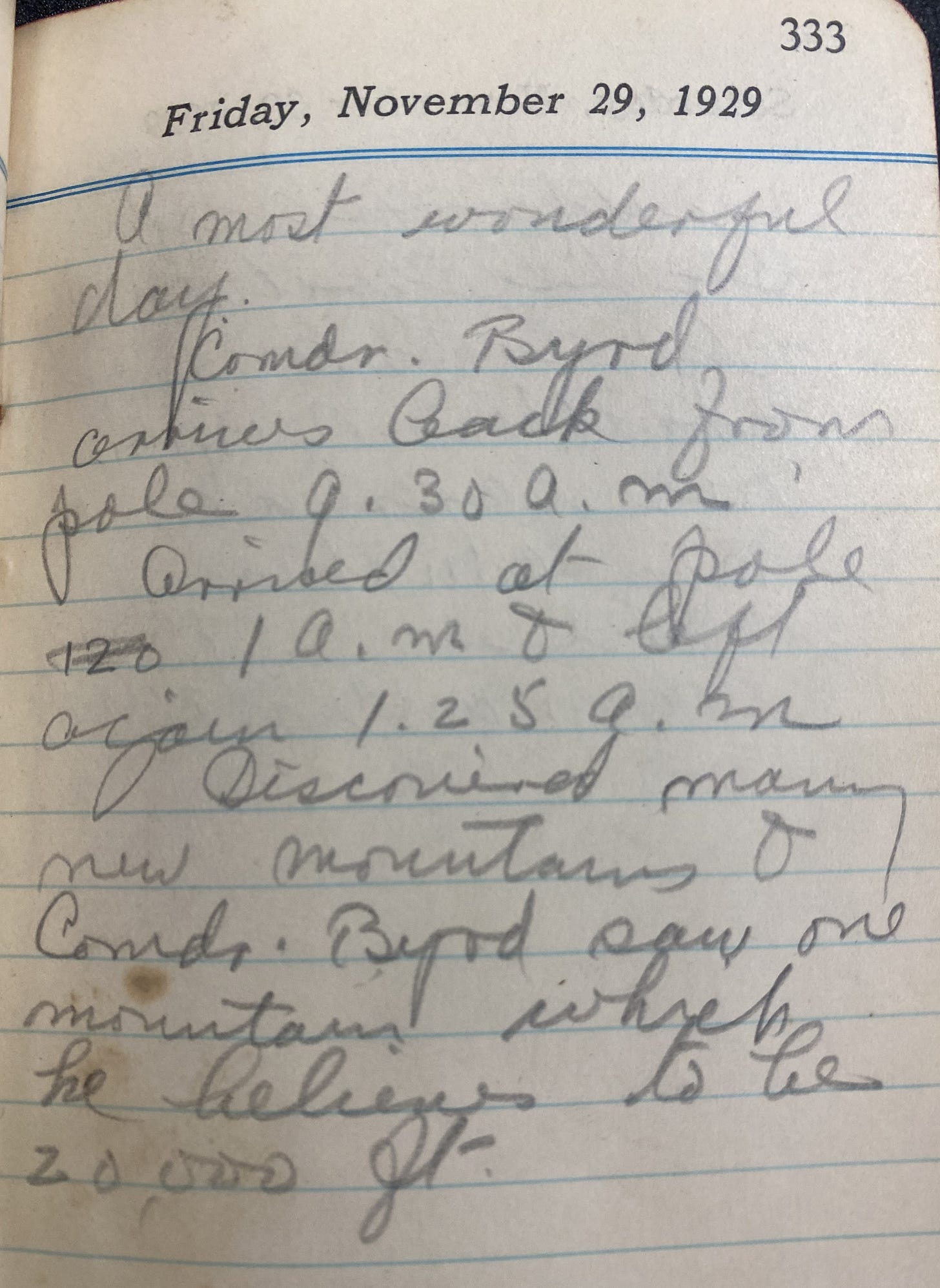

On November 29, 1929, Bursey shares the news: “A most wonderful day. Comdr. Byrd arrives back from pole 9.30 am. Arrived at pole 1am & left again 1.25am. Discovered many new mountains & Comdr. Byrd saw one mountain which he believes to be 20,000 ft.”

Never mind that the tallest point in Antarctica is only 16,000 feet. Bursey’s hero had done it.

(Incidentally, rumors of insanely high mountains made an impression on at least one symbol-conjurer back home: H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness appeared shortly after.)

Of course, something else had happened in 1929. Just a month earlier, the American economy had collapsed. Wilkins, Byrd, and Bursey returned to a much harder world.

Byrd and Wilkins would lead men back to the Antarctic again and again. But this story isn’t about them, really. It’s about the people they inspired, for whom they were icons—symbols, if you will—of human ingenuity, determination, and “can do” spirit.

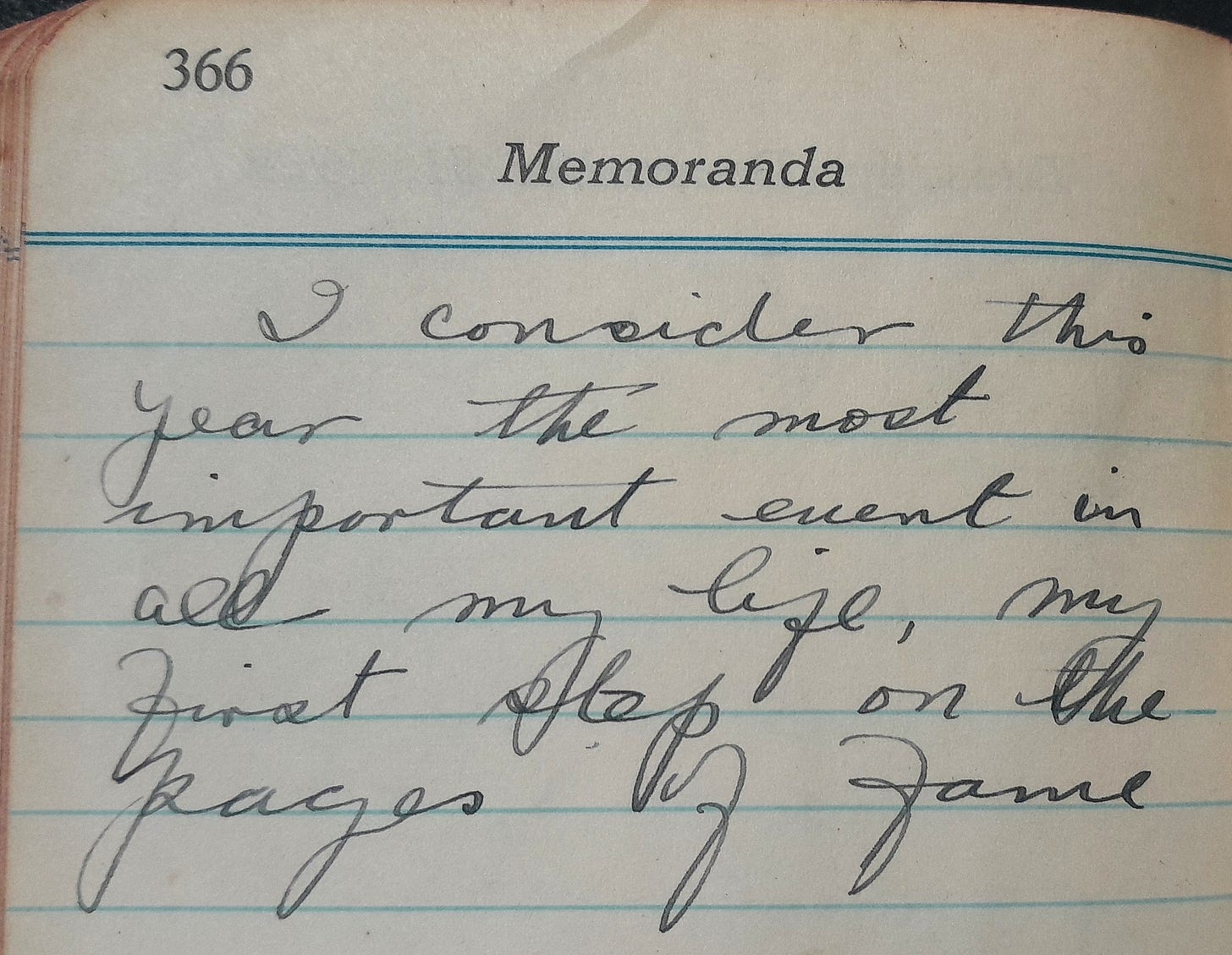

Bursey wrote 365 entries in his 1929 diary. His 366th entry, on a page headed “Memoranda,” reads:

“I consider this year the most important event in all my life, my first step on the pages of fame.”

Bursey, too, returned to the Antarctic and became an expedition leader in his own right. On his way home in 1957, he learned that Admiral Byrd had died.

He may not be famous today, but it seems to me that Jack Bursey lived a big story.

1Jeff Maynard quotes this remark in Wings of Ice (2010), p. 216.