— HISTORY CORNER —

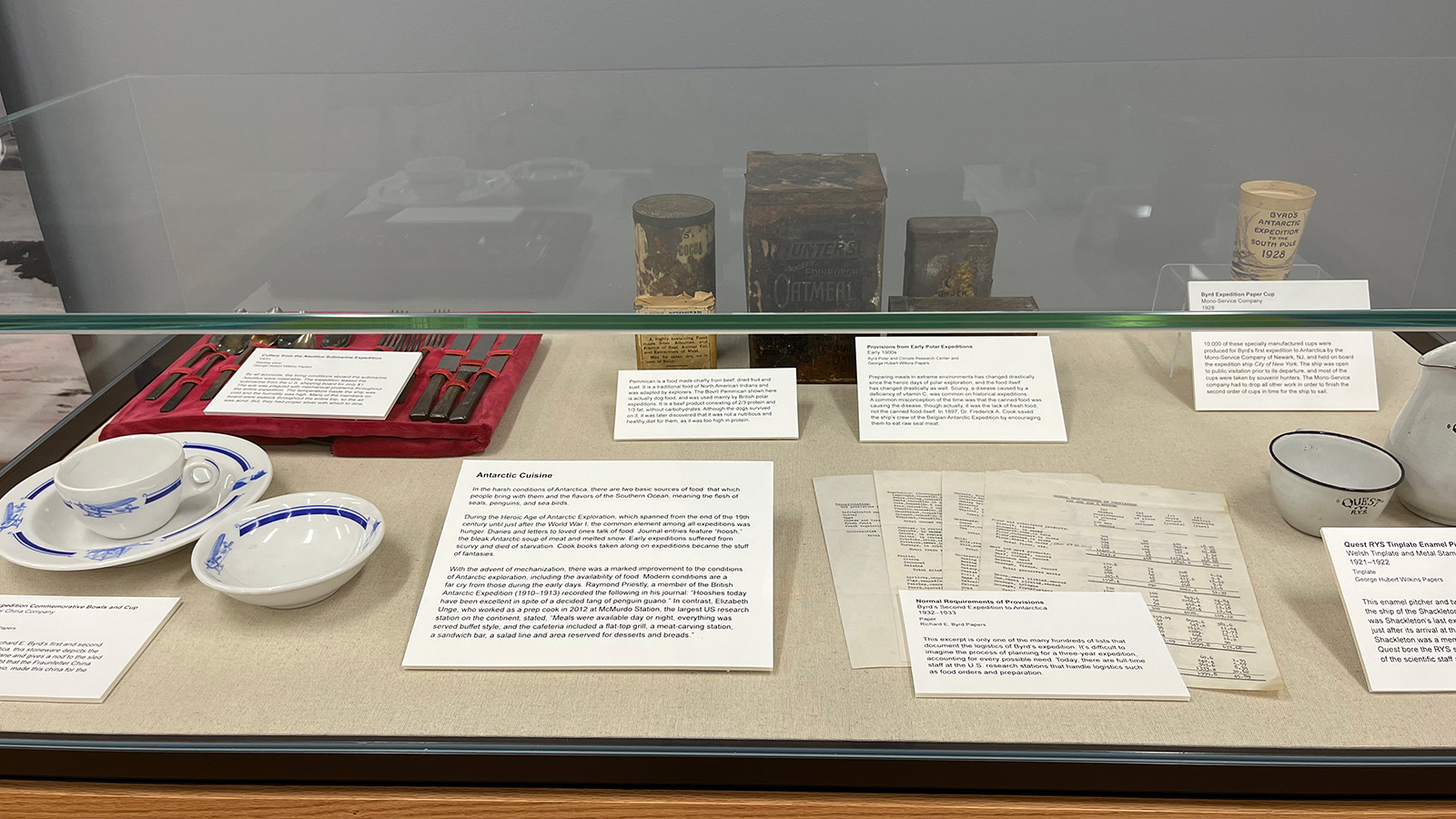

New Exhibit: Food and Dining in the Heroic and Mechanical Age of Antarctic Exploration

By Savannah Stearmer and Laura Kissel

In the harsh conditions of Antarctica, there are two basic sources of food: that which people bring with them and the flavors of the Southern Ocean, meaning the flesh of seals, penguins and sea birds.

During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, which spanned from the end of the 19th century until just after the World War I, the common element among all expeditions was hunger. Diaries and letters to loved ones talk of food. Journal entries feature "hoosh,” the bleak Antarctic soup made of meat and melted snow. People on early expeditions often suffered from scurvy and died of starvation. Cookbooks taken along on expeditions became the stuff of fantasies.

Join us for a taste of how the explorers of the past dined in these harsh conditions.

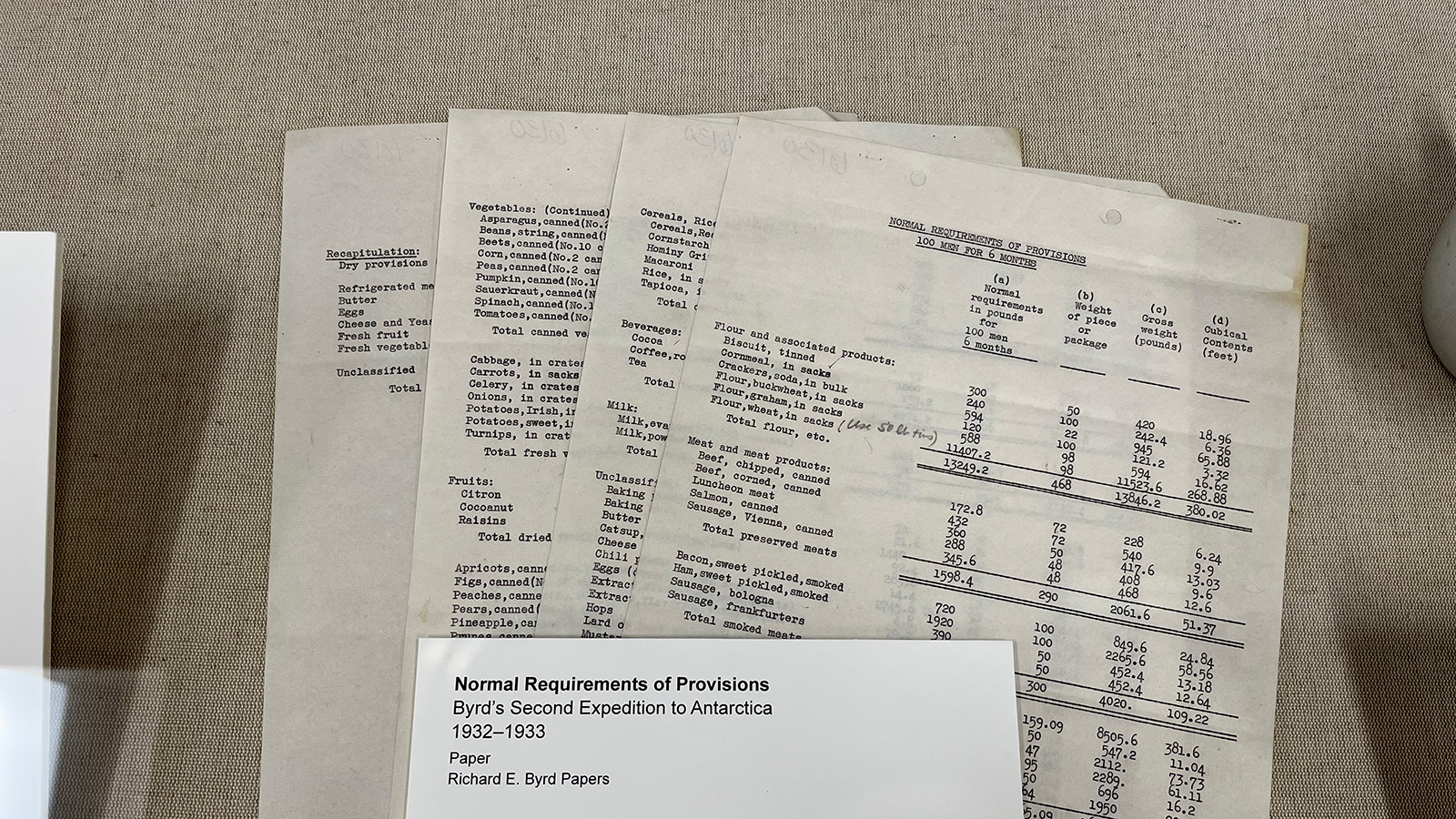

Before the journey

Before even a flake of polar snow hit the heads of the explorers, the fight for survival began with a lot of numbers and some intense planning. This excerpt is only one of hundreds of lists that document the logistics of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s second expedition. It’s difficult to imagine the process of planning for a three-year journey, accounting for every possible need. Today there are full-time staff at the U.S. research stations that handle logistics such as food orders and preparation.

On the expedition

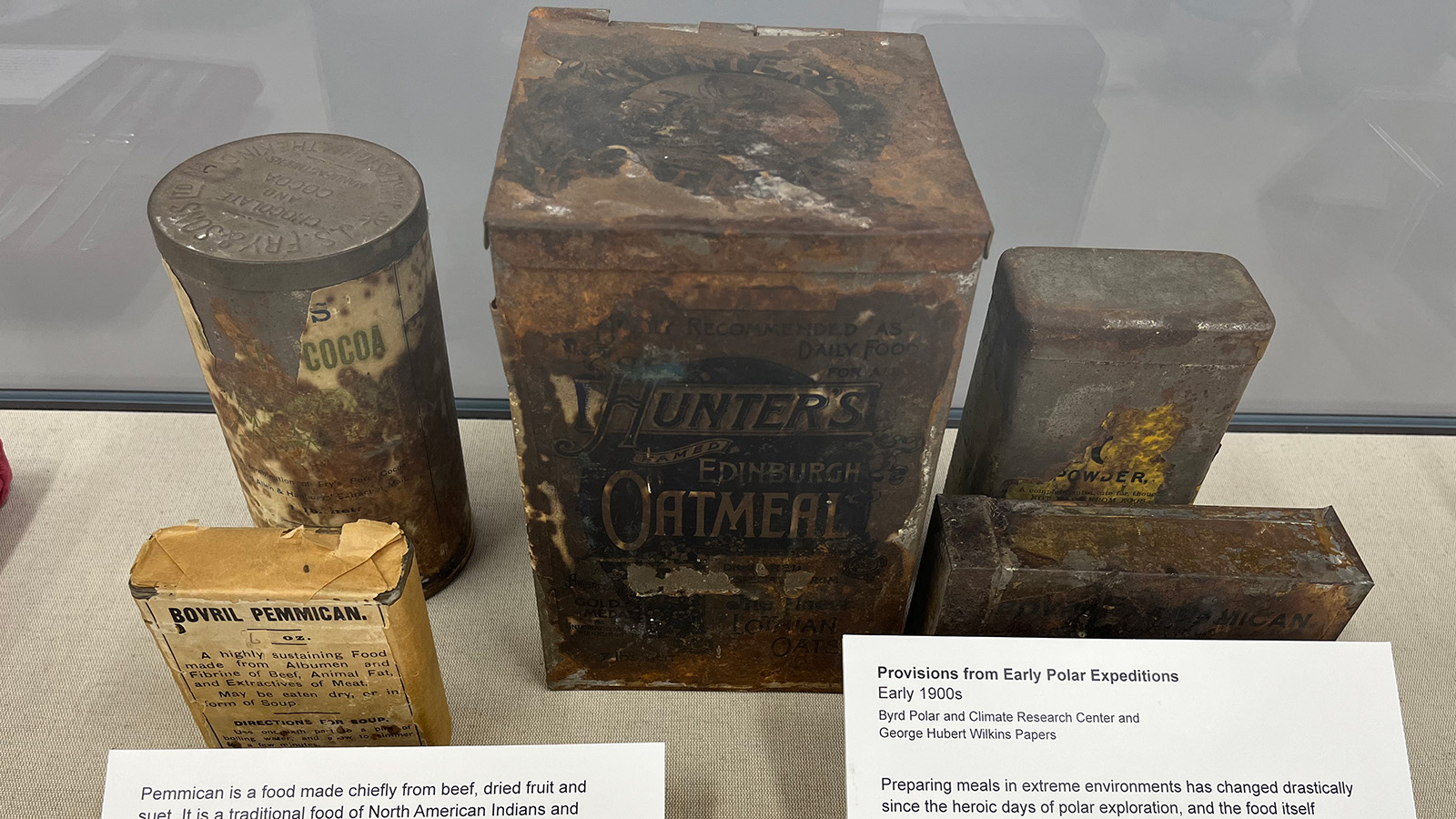

Evidence from the journey can be hard to come by seeing as one of the most important parts—the food—would have been eaten by the hungry explorers. The Polar Archives are fortunate to have a number of these easily-lost artifacts in its collection including the following items.

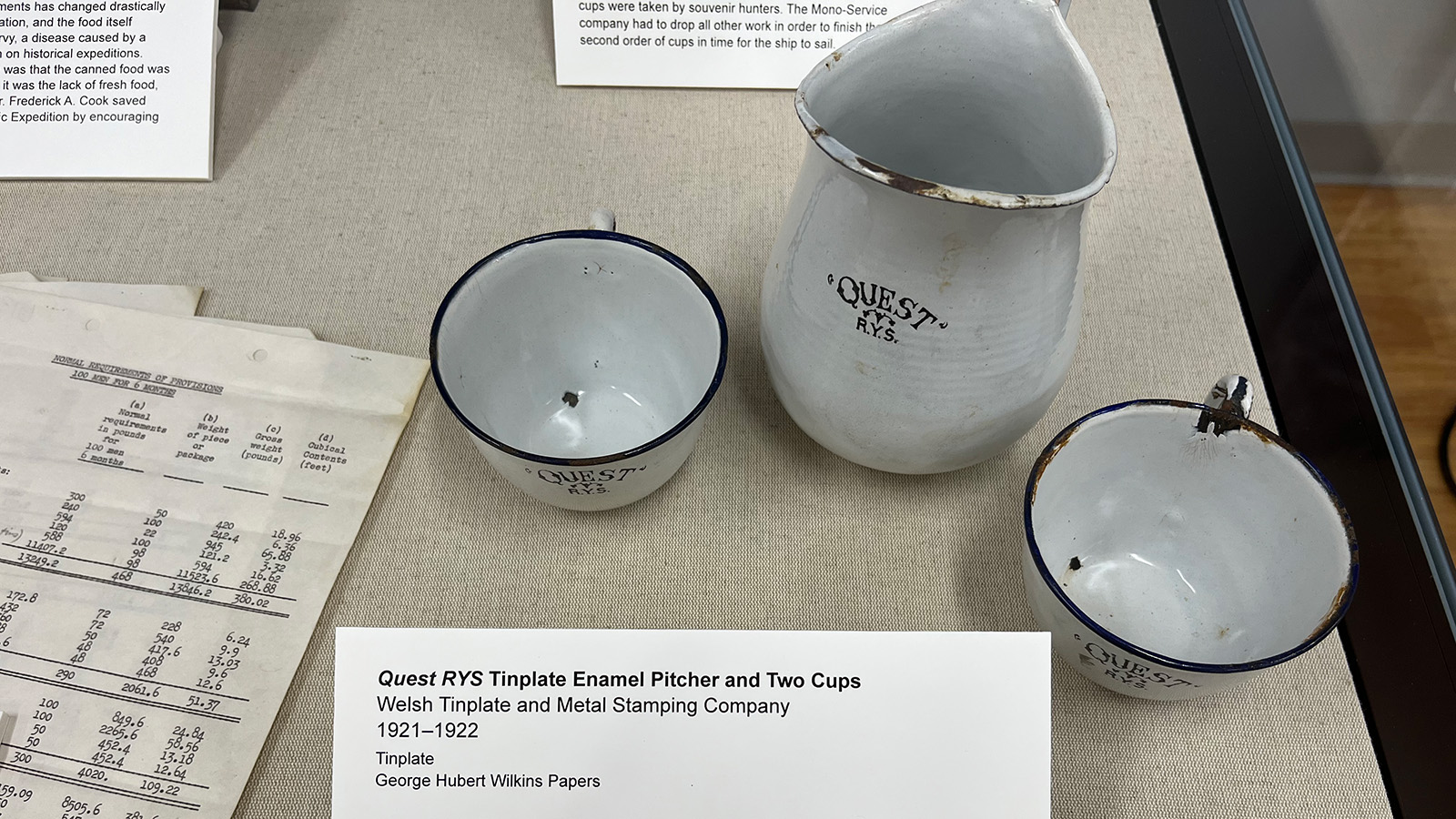

This enamel pitcher and two cups were on board the Quest RYS, the ship of the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition of 1921-1922. This was Shackleton's last expedition; he died while on board the ship, just after its arrival at the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia. Shackleton was a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron, and the Quest bore the RYS suffix. The Polar Archives holds the George Hubert Wilkins Papers; Wilkins served as chief of the scientific staff and naturalist on this expedition.

Pemmican is a food made chiefly from beef, dried fruit and suet. It is a traditional food of North American Indians and was adapted by explorers. The Bovril Pemmican shown here is actually dog food and was used mainly by British polar expeditions. It is a beef product consisting of 2/3 protein and 1/3 fat, without carbohydrates. Although the dogs survived on it, it was later discovered that it was not a nutritious and healthy diet for them, as it was too high in protein.

Humans suffered just as much from poor eating. Scurvy, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, was familiar on historical expeditions. A common misconception of the time was that the canned food was causing the disease, though actually, it was the lack of fresh food, not the canned food itself. In 1897, Dr. Frederick A. Cook saved the crew of the Belgian Antarctic Expedition from scurvy by encouraging them to eat raw seal meat.

By all accounts, the living conditions aboard the submarine Nautilus were miserable. The expedition leased the submarine from the U.S. shipping board for only $1. The sub was plagued with mechanical problems throughout the entire expedition. The temperature inside the ship was cold and the humidity was high. Many of the members on board were seasick throughout the entire trip, so the air was acrid, but they did have proper silver with which to dine.

Back home

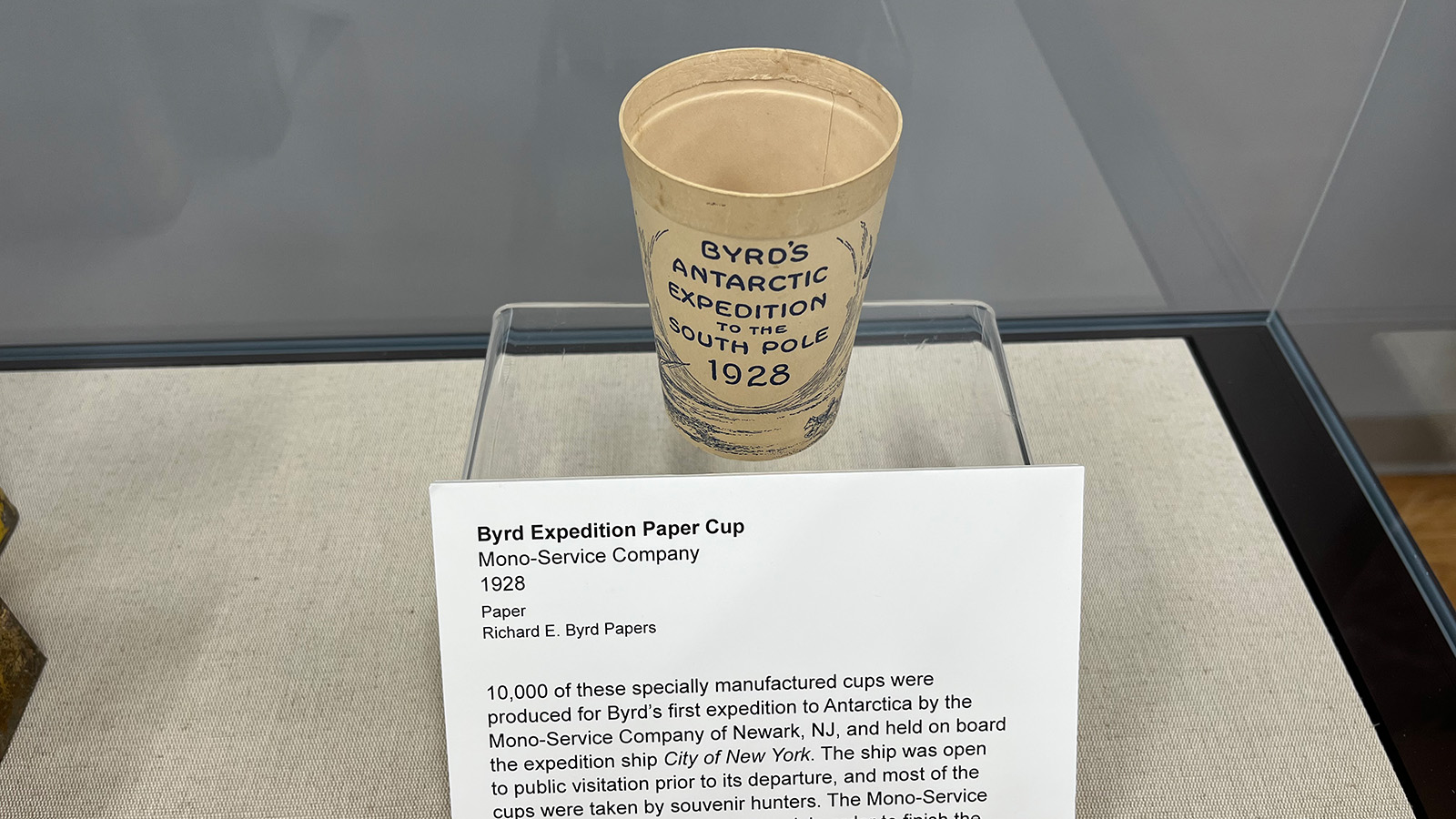

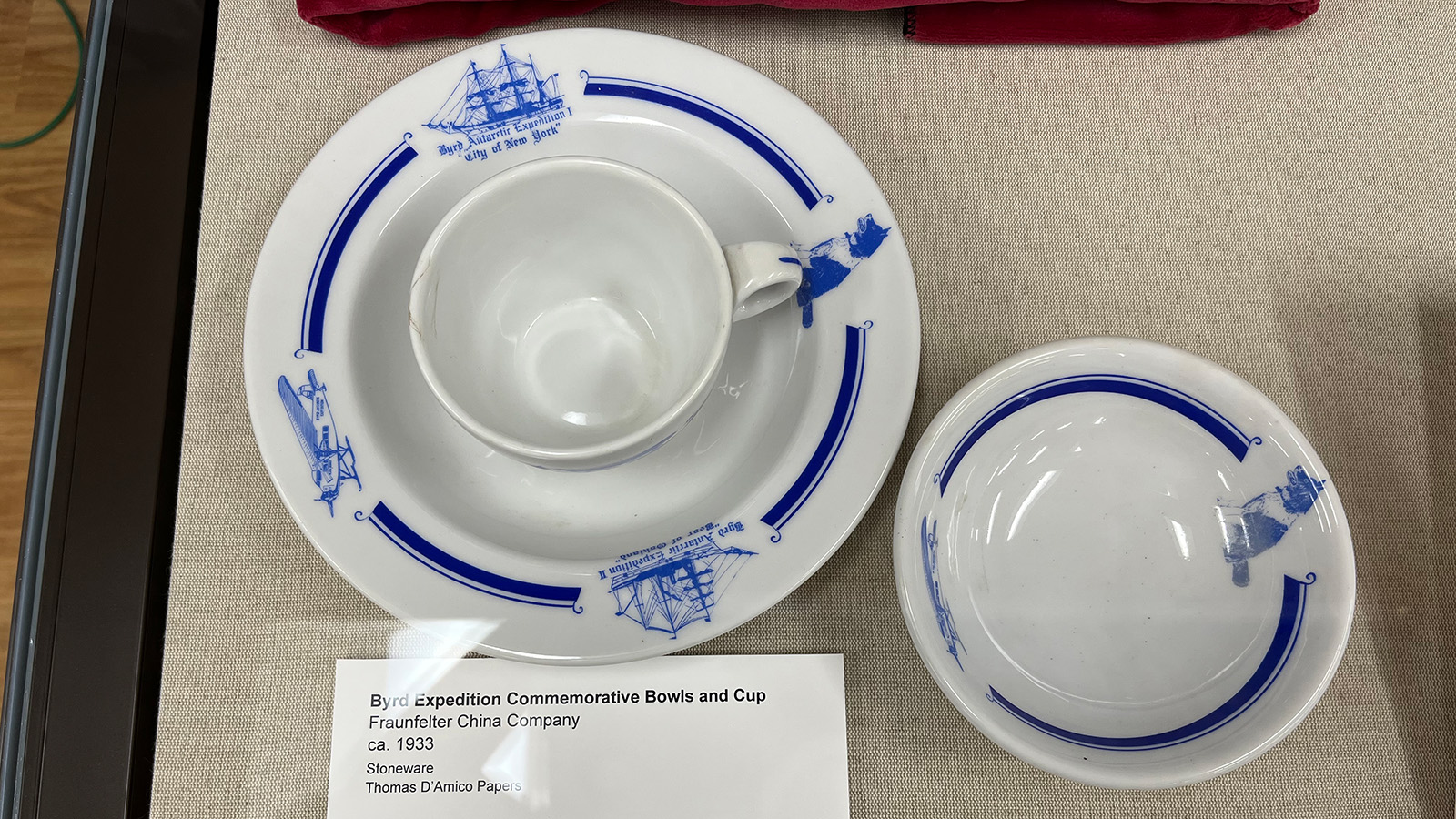

While expedition conditions were often miserable, commemorative items and souvenirs were all the rage as folks back home enjoyed the thrill of adventure, enraptured by tales of rugged explorers on the path to discovery.

10,000 of these specially manufactured cups were produced for Byrd's first expedition to Antarctica by the Mono-Service Company of Newark, NJ and held on board the expedition ship City of New York. The ship was open to public visitation prior to its departure, and most of the cups were taken by souvenir hunters. The Mono-Service company had to drop all other work in order to finish the second order of cups in time for the ship to sail.

Commemorating Richard E. Byrd's first and second expeditions to Antarctica, this stoneware depicts the expedition ships and plane and gives a nod to the sled dog. It is generally thought that the Fraunfelter China Company of Zanesville, Ohio, made this china for the 1933 Chicago World's Fair which was attended by nearly 40 million people over the course of its two-year run. “A Century of Progress,” as the fair was named, was a beacon of hope during the Great Depression, an optimistic promise that the future would be better. This optimism might explain why people were willing to purchase these souvenirs during the Great Depression.

Modern Era

With the advent of mechanization, there was a marked improvement to the conditions of Antarctic exploration, including the availability of food. Modern conditions are a far cry from those during the early days. Raymond Priestly, a member of the British Antarctic Expedition (1910-1913) recorded the following in his journal: "Hooshes today have been excellent in spite of a decided tang of penguin guano." In contrast, Elizabeth Unge, who worked as a prep cook in 2012 at McMurdo Station, the largest U.S. research station on the continent, stated, "Meals were available day or night, everything was served buffet style, and the cafeteria included a flat-top grill, a meat-carving station, a sandwich bar, a salad line and area reserved for desserts and breads."

This exhibit is on display NOW. Schedule your visit today.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Anthony, Jason C. Hoosh: Roast Penguin, Scurvy Day, and other stories of Antarctic Cuisine. 2012: Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Trusler, Wendy and Carol Devine. The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning. 2013: Toronto, Canada: Vauve Press.

Feeney, Robert Earl. Polar Journeys: the role of food and nutrition in early exploration. 1997: Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press