— HISTORY CORNER —

Women Need Not Apply

By Misa Norris

Richard E. Byrd was a famous polar explorer who led seven expeditions to both the Arctic as well as the Antarctic, from 1925 to 1957. His expeditions generated public excitement and a large number of people applied to accompany him, even though the majority of positions were unpaid. The Papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd contain many files of applications from those who wished to go. People highlighted their various qualifications and skill sets when applying, and there are applications for all of the various jobs, such as doctors, dog drivers, and meteorologists. Among these are two folders that contain applications from women who wanted to accompany Byrd on his first Antarctic expedition in 1928 and his second Antarctic expedition in 1933.

Due to the lack of female inclusion on Byrd’s previous trips, the women applicants used various tactics to convince him that they should accompany him. Many of the letters emphasized the capability of women to withstand the physical trials of the expedition. Evelyn Godsey, an applicant from Ohio wrote, “As I understand it, a woman is unable to stand either pole… [but] I cannot understand what the differences are from the women who came over from the old country in caravans to fight for gold than the women of today. Can you?”[1] Godsey reminded Byrd that, despite public perception that women were not suited for the South Pole, they had completed dangerous journeys throughout history and therefore they were able to do it again. Similarly, Rose Sager an eighteen-year-old from New York focused on her physical attributes to prove she was capable. She wrote, “I do not catch cold easily, I have never fainted in my life, I am five feet five inches and my weight is one hundred and thirty pounds.” [1]

Another approach was to prove that women were, in general, the same as men. Nancy Pugh, a thirteen-year-old tomboy from Louisiana asked, “Oh why couldn’t I have been a boy? I am in for adventure wholeheartedly and refuse to stay at home to be a common babbit… At home, I wear knickers and can do anything any boy can.” [1] Alice M. Sigrisil from New York wrote, “In strength, ability, courage and endeavor, they (women) are abundantly qualified, and if any false belief exists regarding their lack of fitness for representation in this important field of endeavor, you have within your power to destroy it.”[1] She challenged Byrd to dispel the existing belief that women were different than men.

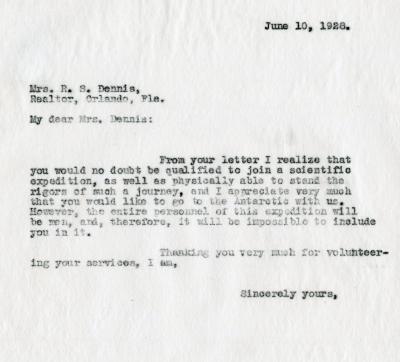

Other women used their professional qualifications as proof that they should be included. Matilda Dennis was a real estate agent from Florida who had spent years working in different lines of business around the United States. Her application included an impressive resume and reference list. She graduated from high school and later took college courses and for a trade paper in Detroit from New York referenced her position as a well-known character analyst and psychologist in her letter to prove she was qualified. She promised to use her expertise to study the expedition team as they experienced physical and mental strain.[1] Her research was to be used for further scientific discovery. Genevieve Wolfe and Madelin Johnson worked as Red Cross nurses with over five years of experience each. Both the highly qualified nurses from Tennessee applied, hoping to provide medical aid for the expedition.[2] Each woman eagerly leant her expertise to the expedition team.

Many of the women simply expressed their passion for exploration and the need for mental stimulation as their reason for applying. Natalie Groden, an applicant from New York wrote, “I am simply fired with the spirit of adventure and am willing to accept the hardships and sacrifices that I know must accompany the trip.” [1] Martha Emerson, a thirty-five-year-old widow pleaded with Byrd to take her because she was “mentally starving” and wanted the education that only the expedition could provide.

Most of the women included in their letter a promise to be useful. Evelyn Godsey wrote, “I will wash dishes, wash clothes, sweep, help with the cooking, keep the home fire burning, type, take dictation, do general office work or do anything I can to help.” [1] Helen Shepard, a sixteen-year-old from New Jersey assured Byrd that she would be “…glad to take care of the food and polish the equipment.” Shephard also volunteered to care for the sled dogs, “I would make a good musher,” she wrote, “but I would even do this to go.” [1] Many also promised not to interfere with the men. Elvy Calloway from Florida promised “not be a nuisance or cause you to regret my presence. I feel that I know my place, and shall do my best to stay in that place.” [2] Each woman was willing to make sacrifices to be part of the expedition

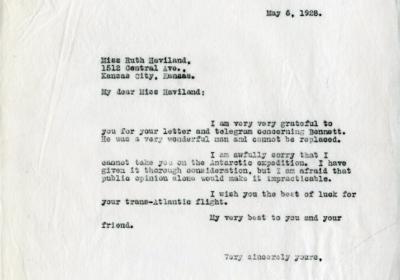

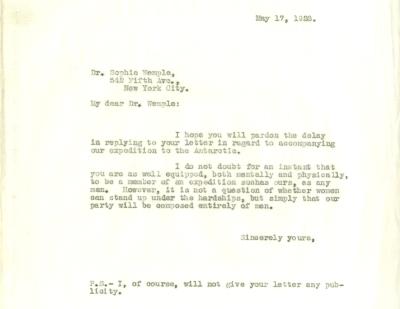

Byrd responded to each letter with the same underlying message. He thanked them for their willingness to participate, assured them that they were qualified for the expedition, then reaffirmed that he was only bringing men. In one such letter, he wrote, “There are no women going to the South Pole on the proposed expedition, therefore I will be unable to take you. I am very sorry that I cannot take everybody who would like to go.” [1] His reasoning for female exclusion was always that the expedition was “strictly a man party.” In response to Matilda Dennis, he wrote, “From your letter, I realize that you would no doubt be qualified to join a scientific expedition, as well as physically able to stand the rigors of such a journey … However, the entire personnel of this expedition will be men, and, therefore, it will be impossible to include you in it.” [1] To Winnifred Webster Harlow his letter read, “I do not doubt for an instant that you are as well equipped, both mentally and physically, to be a member of an expedition such as ours, as any man. However, it is not a question of whether women can stand up under the hardships, but simply that our party will be composed entirely of men.” [1] Despite being qualified, the women were denied simply because of their gender. In a letter different from the rest, he wrote, “I have given it thorough consideration, but I am afraid that public opinion alone would make it impracticable.” [1] He acknowledged that many of the female applicants were highly qualified and capable of withstanding hardships, but this was not enough to earn them a coveted spot.

Byrd remained vague when rejecting female applicants but there are a few possible reasons for their exclusion. The first is that allowing women on a physically and mentally trying journey of mostly men was not supported by the public during this time period. As Evelyn Godsey wrote, people did not believe that the South Pole was a suitable place for a woman. Additionally, there were accommodations that were necessary for a trip including women; there would need to be separate dormitories and restrooms.

Another reason may have been that previous journeys included the King Neptune line-crossing celebration -centuries-old practice that celebrates the first time someone crosses the equator by ship.[3] New members were put through a series of initiation rites that may involve any number of harrowing and embarrassing tasks, such as drinking a homemade concoction and being dunked in seawater. Including women on the trip might mean they would be exposed to the hazing ritual. Images from the Polar Archives document Byrd and his crew participating in the ceremony.

Additionally, other images show crew members dressing up as women for entertainment.

It was likely a combination of all of these factors that kept Byrd from including women in his polar expeditions. The traditional activities that an all-male crew participated in would have had to change if a woman were on board. The lack of public support and the necessary accommodations required to include women resulted in female exclusion from Byrd’s expeditions.

For more information on Byrd’s expeditions visit the BPRC Archival Program.

During Women's History Month, a look back on some of the pioneering women in polar research!

Women in Antarctica: Celebrating 50 years of Exploration from Byrd Center - Ohio State on Vimeo.

Footnotes

[1] Admiral Richard E. Byrd Papers, folder number 4393, SPEC.PA.56.0001, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, The Ohio State University.

[2] Admiral Richard E. Byrd Papers, folder number 6525, SPEC.PA.56.0001, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, The Ohio State University.

[3] Schaefer, Matthew. (2020, January 15). King Neptune Ceremony. The Blog of the Herbert Hoover Library and Museum. https://hoover.blogs.archives.gov/2020/01/15/king-neptune-ceremony/

More History Corner

How did people eat on polar expeditions?

Who was the “ghostwriter” for the Byrd Second Antarctic Expedition?

How did the first all-woman scientific team from the United States come to work in Antarctica?