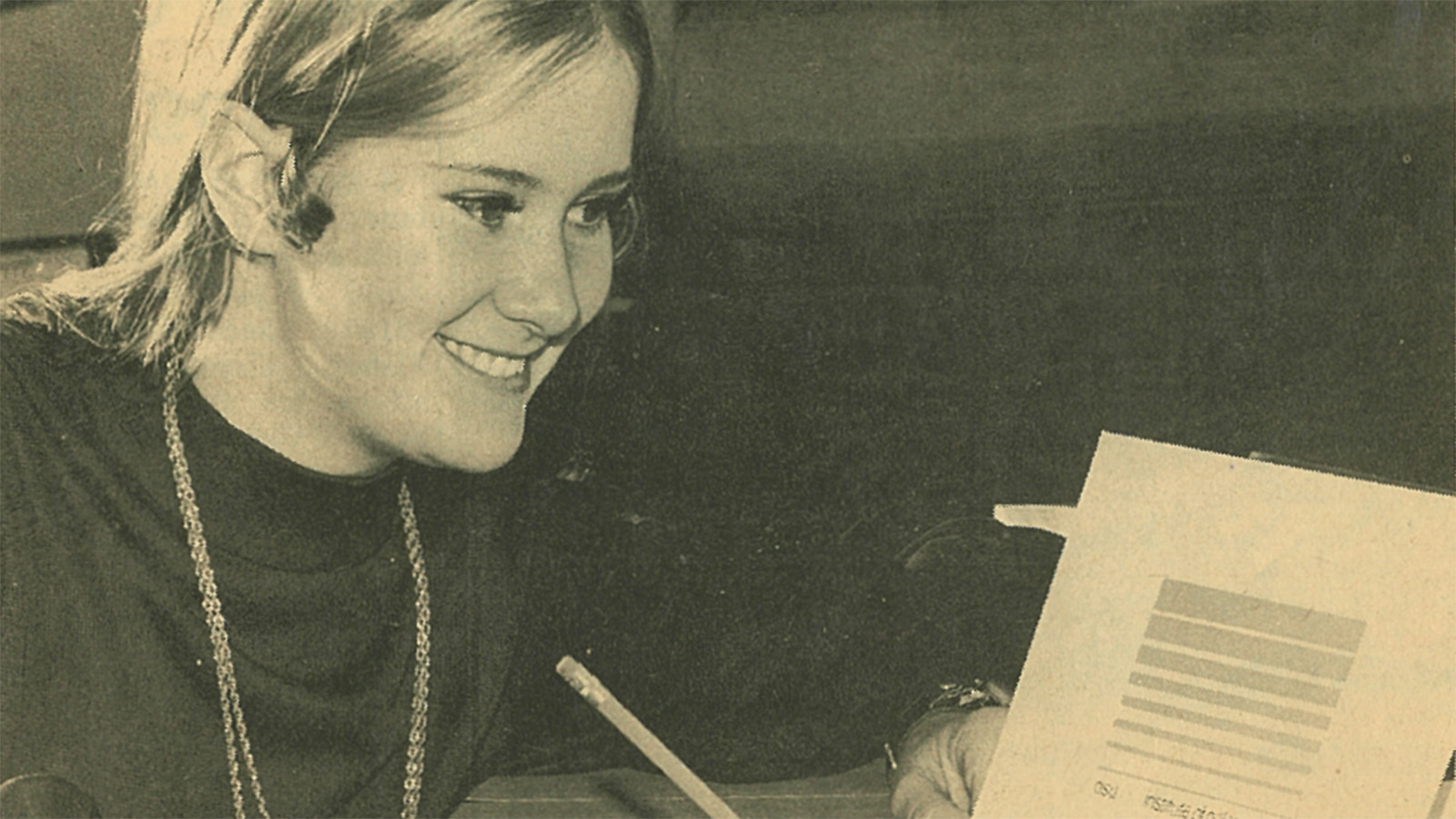

Susannah Casey, graphic design student at Ohio State, circa 1969, holding a picture of her design for the Byrd Center's flag

— HISTORY CORNER —

Who Created the Byrd Center's Flag?

By Savannah Stearmer

This story starts with a roll of toilet paper.

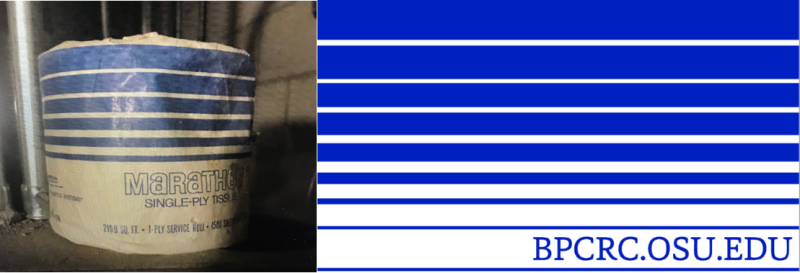

The roll itself is perfectly normal, albeit old and dusty, and utterly insignificant except that it was discovered in a random back closet by Byrd Center staff, prompting the thought, “hey, doesn’t this look like the center’s flag?”

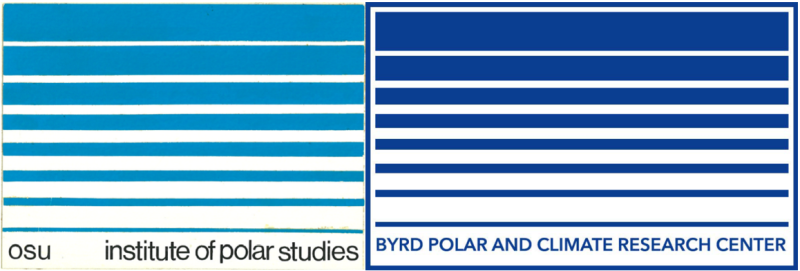

The similarities are, of course, plainly obvious with the design of both objects crafting a striking contrast between blue on white parallel lines set in clean layers of progressive thickness. The similarity was so compelling, in fact, that Byrd Center staff began to wonder if this roll of toilet paper (or one like it) was the inspiration for the flag. Of course, the best way to answer such a question is to ask the creator, but this task was made difficult by various name changes and cross-country travel. In the span of a mere 53 years, as science and technology radically transformed the entire world in its wake, the answer to “who made the Byrd Center’s flag” seemed lost.

Until Dan Casey, bird scientist from Montana working in grassland conservation, received a phone call from one Forrest Schoessow in the summer of 2020.

Forrest, a PhD candidate and researcher at Byrd, had been on the case for months and, after a touch of confusion over “which bird center?” from the ornithologist, Dan passed Forrest onto Susannah Casey, his wife, and the ultimate answer began to finally unfold.

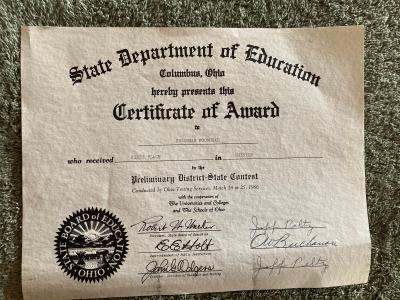

A self-described Ohio valley girl, Susannah grew up in Steubenville, Ohio, a few hours away from Ohio State University where she would eventually go to college. She was a tomboy who played sports, dreamed of becoming a surfer, and had a longtime passion for math and science. “When the wind blows, when nature changes,” she says, “I just think about the physics behind it and how it works.” She read books and magazines on science and won an award in high school for demonstrating skill in the subject, so it’s no surprise that when she finally entered university, she packed her schedule with STEM courses.

The first quarter was disastrous. After graduating third in her high school class with a near 4.0 GPA, she received Cs in both calculus and pre-med chemistry and a mistaken D in art history, huge losses that her A in English Composition could only cover so much. She finished her first quarter with a 2.25 GPA, and it took an entire year for her grades to be corrected and, by then, she’d been effectively turned away from a career in science. Money was an issue, both just from being in college and from the expectations of her background. Finances were finite and the exclusive point of college was to graduate and get a job. With science out of the question, she needed to pick a different path and turned instead to the world of design.

At the start of sophomore year, Susannah entered the graphic design program with the idea to eventually become a medical illustrator. The program was incredibly competitive. All-nighters were an expectation, professors were critical and demanding, and completed assignments were often returned with notes to change anything and everything. Aside from that, the work itself was intense. Every step of the process had to be done by hand using pen, paper, rub on letters (Letraset), and other non-automated tools. Her sophomore year began with lengthy exercises practicing over and over again to draw always-perfect circles with only a compass and a pencil. There were thirty people in her original class. Many of them dropped out. While it took a minute to get her feet under her, Susannah stuck it out.

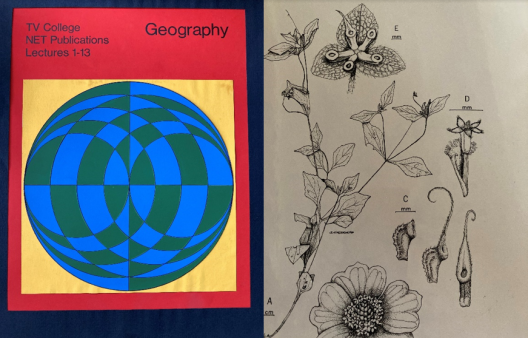

Although it was far from easy, she had a good eye for measurement and a knack for picking up skill sets. She even used her design work to stay in touch with her scientific interests. For one project, she created book covers for a physics and a geography textbook. Sophomore year, she had a work study job drawing plants for a botany professor. The next year, she answered a call for designers from the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center.

Then known as the Institute of Polar Studies, they announced a contest with a $50 prize for the best design of a flag which would be used to identify field parties in the polar regions around the world, defining the Byrd Center before it even earned its current name. The prize was the equivalent of $356.38 today and sixty people submitted designs including Susannah.

Here we learn the root of her design: not a toilet paper roll cover but a vision of life at the poles, surrounded by layers upon layers of ice, a vast expanse of blue and white. Using chart pack, an Exacto knife, and white paper, her process emphasized simplicity and clarity with influence from the German school of thought which encouraged her to use Helvetica as the type face of choice. The design seems to directly reference one of the Byrd Center’s major research projects—drilling and preserving ice cores—although this is pure coincidence as she was unaware of ice cores at the time. Of course, she won all the same and that prize certainly made her life as a poor college student a little bit easier as she prepared for her senior year of college.

That said, the flag design contest was completely overshadowed by the politics of the late 1960s. Amid war protests and the military occupation of college campuses, in addition to the various social injustices facing women at the time, the flag felt insignificant. While she can’t recall how she found the contest or what she spent the prize money on, she remembers watching protests and seeing military from her classroom window, pointing her camera at one of the soldiers, and him pointing a rifle back at her. She didn’t take his picture that day. And then, in 1970, she graduated.

After college, Susannah moved to Colorado and then to Montana and has since spent more than half of her life out West. She got married, had two daughters, and now has two grandchildren. Although she never accomplished her childhood surfer dream, she does live by Flathead Lake, granting her ample opportunity to take a dive whenever it gets too hot. She watches PBS science shows like NOVA and Nature, satisfies her love of color and shape with quilting, and keeps busy with a close-knit bubble of people. Still, even in a long, happy life, it can be difficult to avoid doubt and regret.

She has worked a variety of jobs over the years, some more fulfilling than others, some utilizing her artistic skills or scientific interests, others not. Even decades after leaving, she still always thought “I should’ve been a scientist,” and if it weren’t for that horrible first quarter, she might’ve become one. The idea lingered, bubbling into resentment with no real way to resolve it.

When Forrest contacted her that random summer day two years ago, so much of how she viewed her past transformed. Years of doubt over her flag’s design became satisfaction. Resentment against Ohio State was softened. The disappointment over losing a career as a scientist was replaced by fulfillment knowing that her work was recognized and valued enough for the Byrd Center to seek her out even though she’d lost contact with the University for decades. She had made something that scientists had needed and that was enough.

Nearly sixty years ago, Susannah Casey went off to college during a wildly different era from our modern one. As her own design tools have been made entirely obsolete, thousands upon thousands of tools and processes have radically transformed over the course of a single lifetime thanks to innovation and technological growth. Having seen all of this, she believes that our world, despite its flaws and stressors, still has room for optimism and hope, and that humanity should seek to improve upon what our ancestors have already done. The Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center is proud to honor her as a foundational contributor to the center and hopes the knowledge of who made our flag never again becomes lost.

Special thanks

to Susannah Casey for the interview and the photographs, and to Michele Cook for her photos and the center’s side of the story.