— HISTORY CORNER —

Why are there World War I photos in the Polar Archives?

Twenty-four-year-old Australian photographer and cinematographer Hubert Wilkins spent his time in 1912 in Constantinople photographing and filming the First Balkan War for Britain’s Daily Chronicle newspaper. This work would make him the first person to record footage of wartime combat, and the first person to use a plane as a way of taking war photographs. For the next three years, Wilkins would take this knowledge with him as he photographed the final Arctic expedition of Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson. Meanwhile, much farther south, the Archduke of Austria Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated, beginning a chain of events leading to the start of the First World War.

Stefansson’s outfit hadn’t heard about the war until December 1915. Once the expedition had ended, Wilkins began his journey back home in order to join the war efforts, specifically to see the front lines. Wilkins writes: “I came from Victoria Land in the Arctic to Coronation Gulf, a six hundred mile walk before I got the boat, then to Alaska, Vancouver, to New York, then to London, to South Africa, to Australia and across Australia by railway and then back again to London and France by way of the Cape. It was 12,000 miles back and borth (sic) to Australia, 3000 over the Atlantic --altogether about 33,000 miles to go to war.”¹

Because of his navigation skills and experience flying a plane (though minimal), Wilkins applied to be a pilot in the Australian Flying Corps. Once he arrived in London with other Flying Corps reinforcements, however, he was informed during a physical examination that he was colorblind. Even after going to an optometrist to be sure, he was told to meet with the commander at the Australian headquarters. There, he learned that Captain Charles Bean had chosen him to be an assistant to Captain Frank Hurley, the official photographer for the Australian War Records Section. Hurley also happened to be the photographer on Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expedition and photographed the Endurance as it sat stuck in the ice just a year earlier. Wilkins was pleased with this role and headed to France with Hurley to begin their work.

During their time as photographers for the Australian forces, they each had a separate goal. According to Wilkins: “Hurley was to photograph such scenes suitable to propaganda and press release, while I was expected to photograph actual front line scenes and incidents, showing everything the camera could represent, notwithstanding the conditions.”³ Because of this, Wilkins was very close to massive shells exploding overhead, nearly being shot down while in flight, almost falling out of a war balloon under fire, and being wounded multiple times. In his writings, Wilkins described: “Often it took me hours to get from one shell hole to another say 300 yards away. Several times I would lie out in the open and pretend I was dead to fool the snipers. I always wore my uniform and carried my camera. Sometimes the Germans would wave at me. They knew I was a photographer. Often they shot my camera when they could have shot me.”³ He also mentions: “From the time we reached France in July 1917 until the Armistice, I was present at every battle fought by the Australians --with either the front line or reserve line.”³

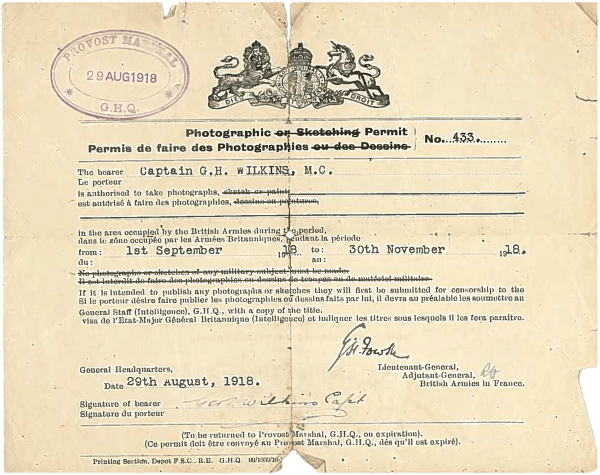

Wilkins received multiple honors for his bravery and service. He earned a Military Cross after serving in France for three months and for bringing back wounded men from No Man’s Land. He also received a bar to the Military Cross for rescuing a section of American troops that were caught in No Man’s Land and captured by the Germans. You can read Wilkins’s recollection of the rescue here (PDF).³ Wilkins was also awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal for his service.

Once the war ended, Wilkins joined Captain Bean on the way to the battlefields of Gallipoli to take photos and commemorate the Australians that fought there for the Australian Historical Mission. In 1921, Wilkins would begin his second polar expedition on Shackleton’s Quest.

To learn more about Wilkins’ exploits in World War I, or any other part of Wilkins’ incredible life, visit the Polar Archives.

Resource List

- 1 Wilkins, George H., World War I: Writings about by Sir Hubert Wilkins, undated, Box 2.1, Folder 27, Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

- 2 Wilkins, George H., Correspondence, 1918, Box 12, Folder 6, Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

- 3 Wilkins, George H., Australia: World War I service in the Australian Imperial Force: documents and an account of his experiences 1919-1930 and undated, Box 1, Folder 14, Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

- Lakin, Shaune A. "Chapter 3: "Great, Stupendous and Awesome": Photographs of First World War Battlefields, 1916-19." Contact: Photographs from the Australian War Memorial Collection. N.p.: Australian War Memorial, 2006. 61-99. Print.