— HISTORY CORNER —

Who was the “ghostwriter” for the Byrd Second Antarctic Expedition?

By Anneke Schwob

Antarctica has been a source of inspiration for writers for centuries. Even when its shores were only glimpsed by the 1838 U.S. Exploring Expedition (also known as the Ex. Ex. or Wilkes Expedition), authors like Edgar Allan Poe (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, 1838) were taken with the possible existence of an Antarctic continent. As the blanks in the Antarctic map began to be filled in during the early decades of the 20th century, there was so much still unknown that pulp fiction writers like John W. Campbell (Campbell’s 1938 novella, Who Goes There?, may be more familiar as the source for the 1982 John Carpenter movie, The Thing) and H.P. Lovecraft (At the Mountains of Madness, 1936) imagined Antarctica as a continent secretly populated by alien invaders and vast underground civilizations. But the fascination with Antarctica wasn’t limited to science fiction fans. The public’s hunger for stories (e.g., Admiral Byrd’s South Pole Game “Little America”) about the Southern continent was an essential part of the ecology of polar exploration, especially for Richard Byrd’s Second Antarctic Expedition (SAE) of 1934. Byrd’s notoriety and inveterate sense of self-promotion was essential for driving interest in the Expedition. Charles Murphy, the chief publicist of the Expedition, however, was the expedition’s author—crafting the discoveries, triumphs and challenges of the SAE into a story that fit the public’s expectations for a heroic polar tale of adventure.

Because they took place in the midst of the Great Depression, before the advent of a formal U.S. government-sponsored Antarctic program, Byrd’s Antarctic expeditions depended heavily on private donations and corporate sponsorship for their funding (to the extent that the authorized map of the SAE was known colloquially as the “Grape Nuts Map”). The Expedition—and Byrd himself—also received funding and promotion through media and publishing contracts with Columbia Broadcasting, Paramount Pictures, the New York Times and other media outlets. Historian Robert Matuozzi has suggested that these media contracts and radio broadcasting schedules might have meaningfully shaped the way that the expedition was run. The broadcasts were meticulously scripted by Charles Murphy. Although they were planned in advance, they were intended to seem spontaneous and, above all, entertaining. Over time, a distance grew between day-to-day life at Little America and the public’s vicarious experience of Little America. While the expedition members suffered from the sort of depression, lethargy and in-fighting that one might expect from living in cramped, frigid quarters for months on end with no sunlight, the Columbia radio broadcasts emphasized the men’s joking camaraderie and implied that important scientific discoveries were being made every day. [Columbia Broadcast Press and Journal Entries. July 11, 1934]

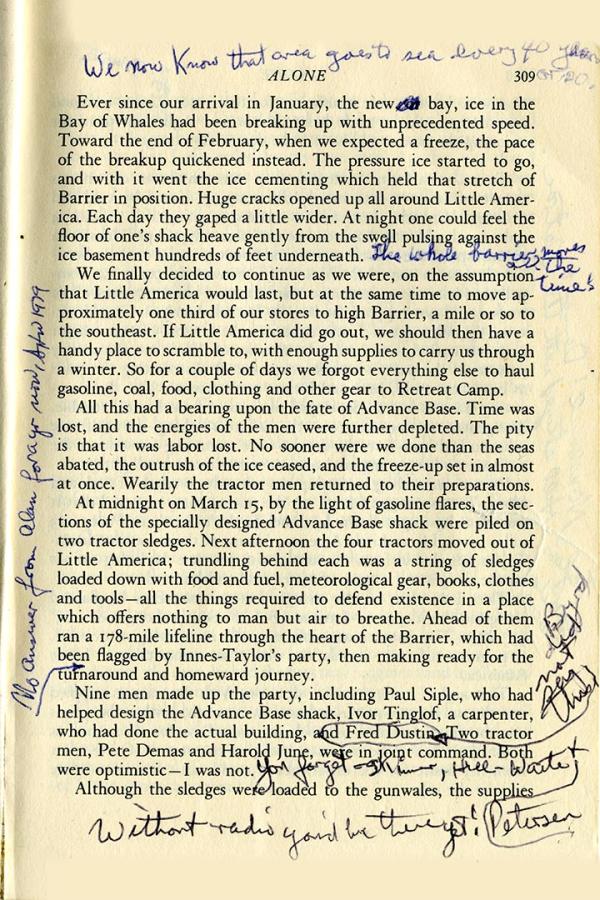

The distance between the story of the SAE and the truth was never greater than in the days surrounding the dramatic rescue of Admiral Byrd from Bolling Advance Weather Base in August 1934. Byrd had taken up a solitary posting at Advance Base on March 28, and intended to stay in the small, poorly ventilated hut for the entire winter night in order to conduct meteorological readings. Over the course of several months, however, the hut’s poor ventilation him weakened from chronic carbon monoxide poisoning. (Byrd’s time at Advance Base is chronicled in his 1938 memoir Alone). As Byrd sickened, his transmissions from Advance Base grew less coherent and those at Little America grew increasingly worried. Murphy’s radio transmissions during this time, however, gave no indication to the public that anything was wrong. The story that Murphy and Byrd had crafted—of Byrd, the polar hero, going out alone onto the ice for the sake of scientific discovery—had no room for a weakened man who would endanger his subordinates with a rescue attempt. When the rescue attempt was finally executed, however, the story had to change yet again. In his radio dispatch from August 12, the day after the rescue party reached Advanced Base, Murphy suggests, “For some time it was evident something was wrong. Your correspondent has had a long and intimate acquaintance with Admiral Byrd: and as these conversations progressed during June and July he sense, more through intuition than anything else, that something had gone wrong at Advance Base.” In this radio dispatch, Murphy shifts the narrative: rather than Byrd, the noble polar hero, who would die in the name of science rather than endanger his men (joining the long legacy of polar explorers—Scott, Shackleton, Lawrence Oates—who had given their lives in the name of Antarctic exploration), he draws attention to the rescue party. “That’s the sort of man who completed this splendid journey to Advance Base,” he writes, “who quietly declined to be discouraged by two failures – who blasted the ancient superstition [that] a protracted winter journey in the Antarctic is a bold invitation to disaster.” The rescuers, he says, “decided it was better to err on the side of honor and affection rather than prudence.” [pages 2, 3, 5 of Aug 12 1934 press dispatch]

How did the other members of the SAE react to Charlie Murphy’s ghostwriting their lives at Little America? It seems that, in one way or another, various expedition members tried to both take back control over their own narratives and get a piece of the lucrative publishing pie. Once the expedition members had returned to the States, Murphy’s editorial tendencies became a source of friction between him and Byrd, who felt that his friend was taking an overly liberal approach to ghostwriting Alone, to the extent of even crafting Byrd’s diary entries from whole cloth. The cantankerous Amory “Bud” Waite, a radio operator and one of the three men who ventured out by tractor to rescue Byrd from Advance Base, countered what he seems to have perceived as an overly romantic narrative sensibility with cold, hard facts. The Byrd Archive contains, among Waites papers, various magazine articles and the Reader’s Digest version of Alone, in which Waite has carefully circled and corrected all the factual errors.

Other members of the expedition met story with story. Being in Antarctica, it seemed, turned all the SAE expedition into writers. Like the Shackleton expedition, who wrote the Polar Times as a way to keep themselves busy during the dark, overwintering months, the men of the SAE undertook the publication of the Barrier Bull, a Mad Magazine-esque endeavor that combined poetry and fiction with gossip about crew members and its production or circulation. It was so popular that the restriction of copies due to limited mimeograph paper seems to have caused a minor stir. In the May 26th, 1934 issue, one writer (anonymized as “Uncle Peter,” possibly Epaminondas “Pete” Demas) tells the “Bedtime Story” of another polar expedition, in which a supply ship is wrecked and all its stores of alcohol are lost. (Access to alcohol was an ongoing point of contention among crew members.) The crew was devastated. Not because they were looking forward to drinking the alcohol, though. Rather, they needed it to keep the ink in their pens from freezing in the Antarctic winter—since, the author adds slyly, “Every hero was very busy writing a book about himself as well as separate books about each of his fellow heroes. Every day, besides writing up his diary, each one wrote radio messages to be sent to all of his relatives and friends to let them know that he was well. Each one wrote newspaper articles and poetry daily and hours and hours were spent practicing signature writing.”

About the Author:

Anneke Schwob is the winner of the 2019-2020 Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program research award.

Schwob’s research, supported by the $5,000 grant, will include studying the papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd, particularly the documentation of his solitary journey and four-month stay at the Bolling Advance Weather Base in 1934.

Schwob is a doctoral candidate whose research interests include American literature and science, the birth of American conservation movements, periodical studies and natural history. Archival portions of her research have been supported by fellowships from the Science Fiction Society, the Graduate School at UNC, and the Mary and David Harrison Institute at the University of Virginia. Her dissertation, In Situ: Environmental Management and the American Literary Imagination, explores how popular, serialized narratives used the scientific project of wilderness exploration and conservation as a tool of literary nationalism in the decades immediately preceding the foundation of the National Parks Service.

Further Reading:

-

Robert N. Matuozzi, “Richard Byrd, Polar Exploration, and the Media,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 110 No. 2 (2002): 209-236.

-

Yaël Schlick, “Writing Alone together: Richard E. Byrd’s Antarctic classic and the challenges of reading collaborative autobiography,” The Polar Journal Vol 6(2) (2016): 328-341.