— HISTORY CORNER —

They greeted me with well I suppose you know that Shackleton’s dead

by Dr. Marissa Grunes

Land ho! Men scurried up on deck, squinting to south. There it was, a dark smudge on the horizon. Even aloft in the rigging, keen eyes could have mistaken it for one of the threatening clouds that had chased them from Rio de Janeiro. The weather had been so bad that it was early January and they still hadn’t had Christmas dinner. They would celebrate the Nativity on that island, hundreds of miles from any other human habitation.

South Georgia.

Many aboard the Quest had never seen it before. A few had visited. And one of them had staked his life and the lives of 27 other men on its icy shores.

Ernest Shackleton stood on deck, looking out at the island that had been his salvation. He was 47 years old, though he looked older. His will had always been stronger than his health.

Barely six years earlier, he and a few companions had landed on that island. Three of them had crossed its unnamed glaciers by moonlight, arriving at Stromness Whaling Station at first light after 36 sleepless hours. After surviving nearly two years stranded in the Antarctic, finally, the crew of the Endurance would be rescued.

Shackleton’s second-in-command, Frank Wild, had been on the Endurance. Now he walked over to the Boss and stood beside him. The island was unimaginably small. But he too owed his life to the whalers of South Georgia. They’d already agreed they would have dinner that night ashore. And, the next night, Christmas dinner for the men.

Shackleton knew the island better than anyone alive. He stayed on deck, pointing out features as the ship approached and telling the crew stories of his past visits.

He hosted a game of cards that night. It was just like old times. Wild remembered the raucous card games in Tent Number One back at Patience Camp on the sea ice. After the Endurance sank, cards were a way to distract the men from the pitiless ocean lurking just a few feet beneath them. Camped on bare ice, the men of the Endurance had gone to sleep each night knowing the floe might crack under their tents, drawing them into the black waters that had taken their ship. In a different way from South Georgia, cards too had saved their lives.

After cards, everyone on the Quest went to sleep early, dreaming of tomorrow’s Christmas dinner.

The Boss is back!

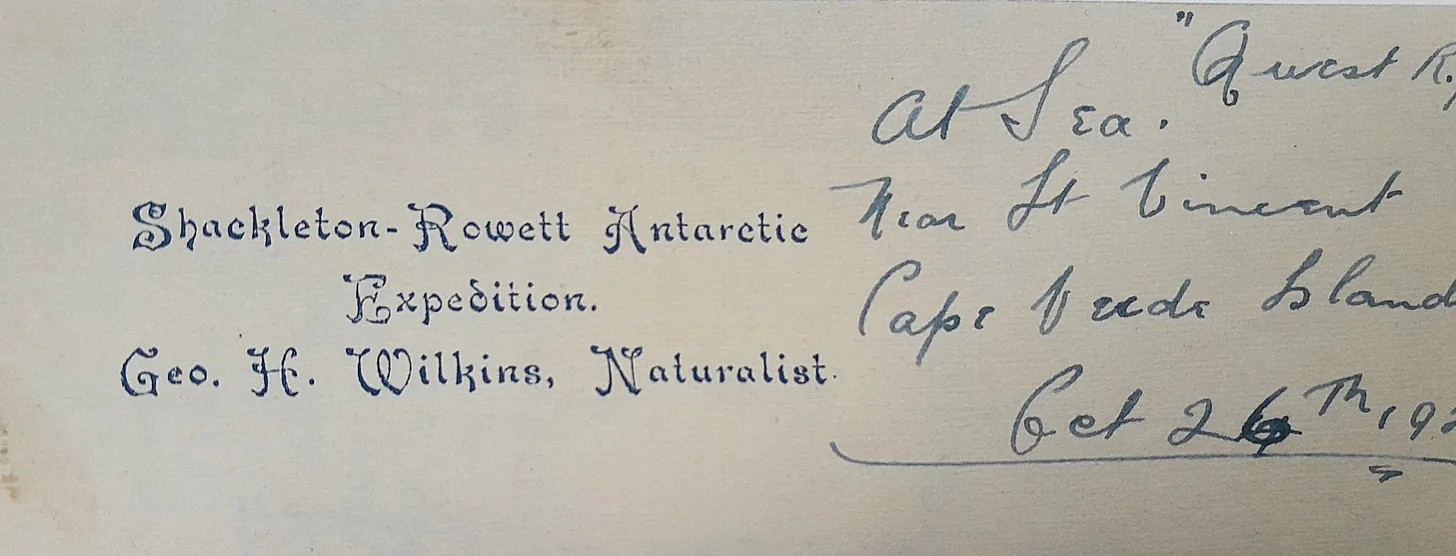

At the whaling station, everyone knew he was coming. Two men from the Quest had arrived early—a naturalist and a geologist—who were tired of waiting around in Rio and wanted to do some real scientific work.

One of these men was George Hubert Wilkins. He was still young, hungry for adventure and fame. He’d find both, in time, as a daring aviator and visionary explorer. Right now, though, he was frustrated.

Everyone worshiped Shackleton. Wilkins sang a different tune. “I am not very much impressed with Sir Ernest’s leadership,” he’d written to his mother a few months earlier. “He cares only for newspaper notices & money.” Still, Wilkins had to admit, “he has a way of interesting people.”

Wilkins had enjoyed a few weeks of freedom with the expedition geologist, George V. Douglas, wandering around South Georgia cataloguing birds and plants, mapping the island’s geology, and taking photographs. Wilkins had already earned distinction as a photographer during WWI, and now he saw slaughter of a different kind.

“I feel disgusted in a way at taking pictures of [the whale butchering],” Wilkins wrote in his diary on January 2, 1922. “but then it shows the work that does go on & the whales marvels of creation that they are.” Wilkins himself killed birds on South Georgia for scientific study, but he had always prized the enlargement of man’s mind above the enlargement of his wallet.

If he read Shackleton’s account of the Endurance, he would have known that the Boss shared his unease around the slaughter at South Georgia. “Here we saw the first evidence of the proximity of man,” Shackleton had written, “whose work, as is so often the case, was one of destruction.”

Finally, a day late, the Quest pulled into the harbor, its flag at halfmast. Immediately Wilkins knew something was wrong.

As he clambered aboard, he was given the news.

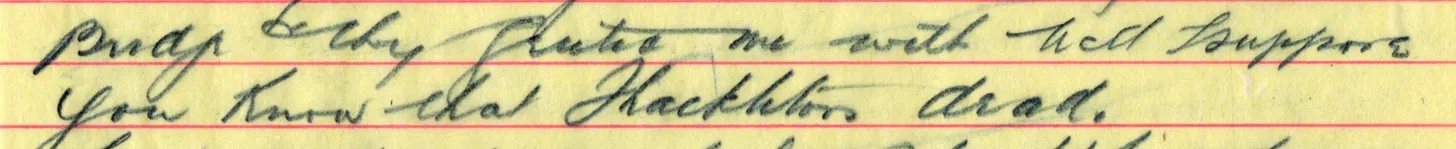

“They greeted me with well I suppose you know that Shackletons dead,” he wrote. “I nearly dropped Why Shackleton dead it was the last thing I would have thought of.”

In the same diary entry on January 6, Wilkins records the first time he heard the story.

The day before, he was told, the Boss “had been in the best of good health & spirits so far as they knew.” After the game of cards, Shackleton had retired early. Around 3am, Alexander Macklin saw the Boss’s light burning and stopped by his cabin. Macklin had survived the wreck of Endurance as well, and like many others, would have followed the Boss anywhere. Shackleton was awake, and had a pain in his shoulder. He asked for a draught to ease the pain.

“M went off to his cabin to prepare the draught thinking that it was nothing serious,” Wilkins goes on. “The Boss took it from him drank half of it & letting the glass drop out of his hand fell back on the pillow dead.”

Telling the story years later, Wilkins would acknowledge the elephant in the room: Shackleton’s drinking. With the game of cards doubtless there was whiskey, and when Macklin went to the Boss’s cabin that night, he challenged Shackleton to stop.

“[Macklin] said in a joking way, “You can’t take sleeping powders. You give up good living and you can sleep."

“Shackleton said, "You always tell me what I have to give up. First it was drink, and now what next?””

According to this later account, Macklin mixed the sleeping draught anyway, but the moment it touched Shackleton’s lips, he fell dead. Macklin half-feared he’d poisoned the Boss by accident. The cause of death was later declared to be heart failure.

Why does young Wilkins not mention the drinking in his diary? It was no secret, and Wilkins had been candid—even harsh—about the Boss in earlier letters. After Shackleton died, though, Wilkins’s tone changes. He records feeling “shocked.” He sounds even a little lost.

In his earlier criticisms, Wilkins had been brash, confident, superior. Was that bravado? Young Wilkins saw himself as leading a new generation of explorers—the brave aviators destined to replace old and inefficient men like Shackleton. Yet when that great hero died, it must have felt like losing a father. Wilkins was thrust forward, alone.

“I had had only 3 or 4 long confidential talks to him,” Wilkins confided in his diary. “He had already told me of his start & had given me some good advice & what he thought of me & my opportunities in Expeditionary work which I am glad to say was encouraging.”

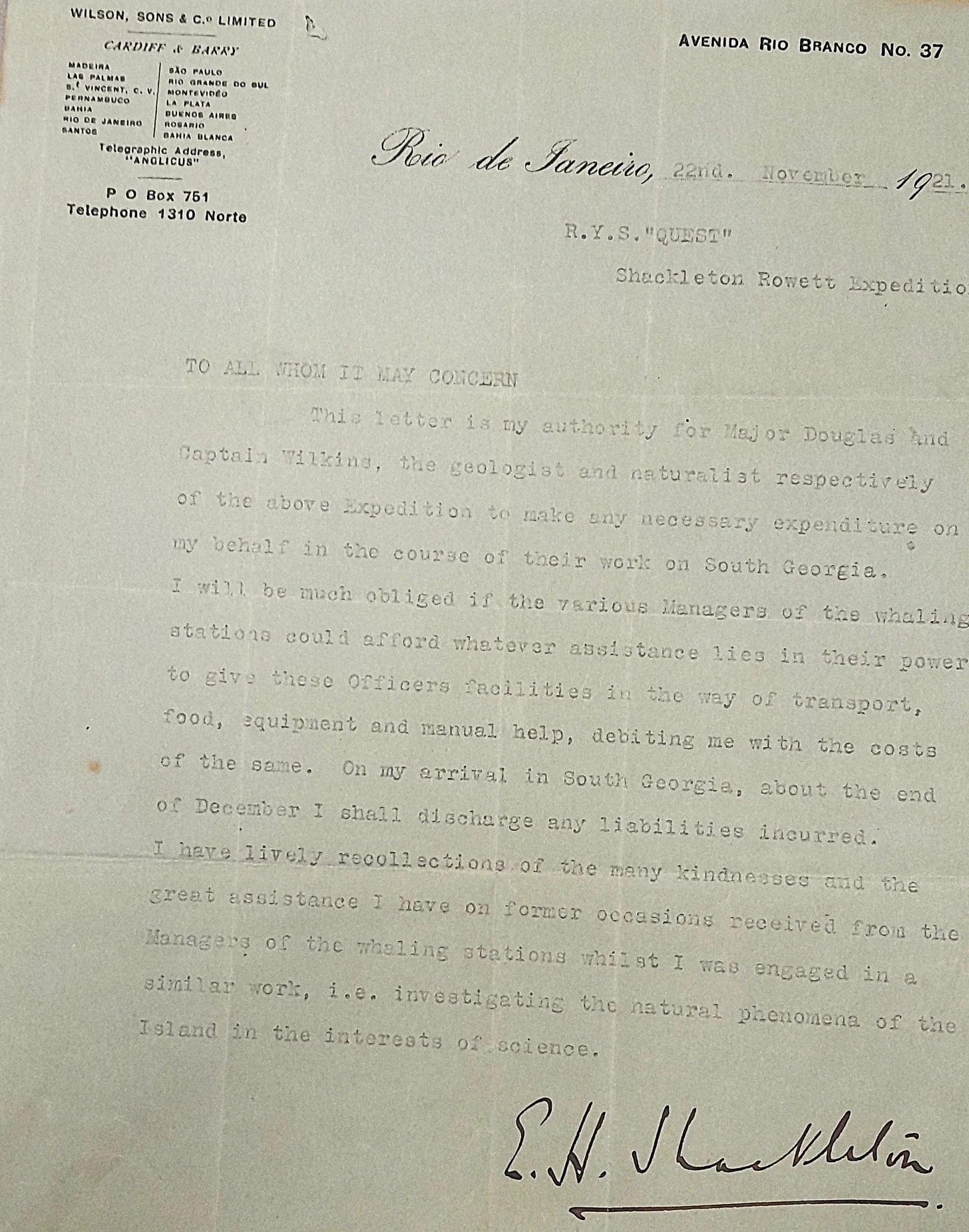

Wilkins wanted to take an airplane to the Antarctic, but had not had the chance to ask Shackleton about it. Before Shackleton died, however, the Boss had written a letter giving Wilkins and Douglas authority to purchase whatever they needed to do their work on South Georgia. It was a mark of trust from a great man. Now was the time for Wilkins to step out of the Boss’s shadow and make his own move.