90-year-old Henry Brecher at the Nordkette peak in Innsbruck at 2300 meters above sea level. Image credit to Emily Mazan.

— HISTORY CORNER —

The Traveler

One Man’s Journey from Austria to Antarctica to Ohio

By Savannah Stearmer

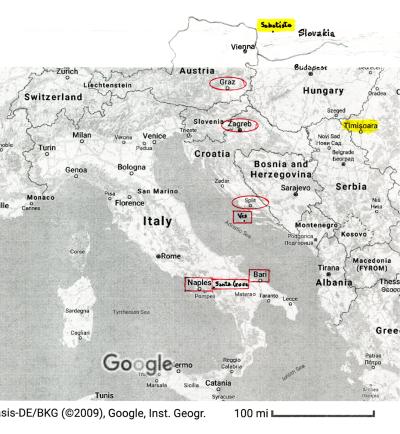

The year was 1938 and a young Heinz (Henry) Brecher lived in Graz, Austria with his family. Henry would go on to travel the world on research missions from Antarctica to the Arctic, from high mountain areas across North and South America, all the way to China doing field work with the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center. In this moment, however, he was five years old, and his entire world was Graz.

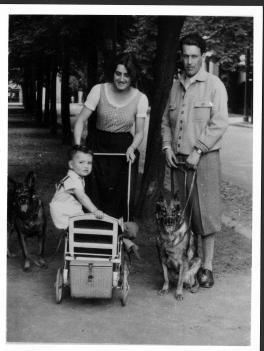

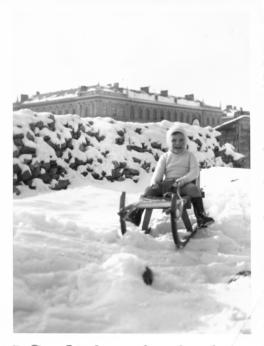

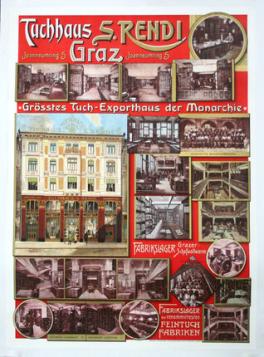

His father worked in the family business in town—the largest textile merchant in the country—called Tuchhaus S. Rendi. Much of his extended family lived in town as well. Some lived in the apartments directly above Tuchhaus S. Rendi in the center of the city while Henry and his parents lived in an apartment block a little farther from the center of town. There was a park nearby, a good sledding hill close to the local university, and plenty of dogs around as his father was the family dog trainer. It was a good life for a five-year-old, full of joy and family, but the year was 1938 and the Brecher family was Jewish.

In March, Nazi Germany annexed Austria, and within a week, Henry’s parents sent him to live with cousins in Zagreb, Croatia. His parents stayed behind, intending to follow as soon as they sorted out family and business affairs, but time ran short, and the Nazis closed Austria’s borders. Henry’s parents were trapped along with tens of thousands of other Jews.

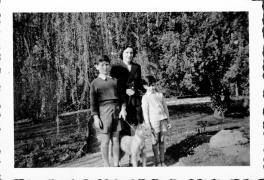

Over 100 miles away from home, Henry was safe. It was a fragile safety, hinged on the mercy of war-mongering Nazis, but safety, nevertheless. He had a family, another dog, a tutor, and plenty of new parks to run through in Zagreb. Then in 1941 – only three years later – Germany invaded Yugoslavia and shattered this fragile peace. Henry was sheltered by the Rosenthal family—old friends of his parents—who lived in Split in Italian-occupied Croatia, over 200 miles away from Zagreb. They lived there until 1943 when the capitulation of Italy and the occupation of Split by the Germans forced them to flee to Bari, Italy where they found temporary refuge in a displaced persons camp along with thousands of others. Eventually Henry and his foster family (except for Rudolf Rosenthal, the father, who was deported earlier by the Germans) made it to Oswego, New York on a United States government-sponsored transport operation known as “Token Shipment.” For the first time in seven years at the age of 12, Henry was finally safe. Sadly, most of his family died during the Holocaust, including both of his parents who died in 1942 in a Polish concentration camp.

For the next six years, Henry grew up in New York, attended a Quaker boarding school where he excelled at math, and then decided to pursue a career in mechanical engineering. At 18 years old, Henry attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute where he discovered that being good at math in high school was very different from being a high achiever in engineering. While struggling through his degree, Henry joined the Reserve Officers' Training Corps at Rensselaer and was commissioned into the United States Air Force. Henry was assigned to the Air Technical Intelligence Center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio where he sat in an office all day handling reports. He hated it. The moment flight training became an option, he leapt at the opportunity but ultimately decided that a military career was not for him. After release from active duty, Henry went to work for the Pratt & Whitney aircraft company as an engineer, where he pushed more pencils, made a few friends, and waited for something better.

In 1959, four years after Henry graduated from college, a friend at work mentioned a job ad and something about research in Antarctica. Henry couldn’t care less about the details; Antarctica sounded better than anything else he’d tried, so he submitted his application. As it turned out, the advertisement was looking for scientists to study auroras. Although Henry was not strictly qualified, the small pool of applicants meant that Henry, along with one other mechanical engineer and two physicists, was headed to Antarctica.

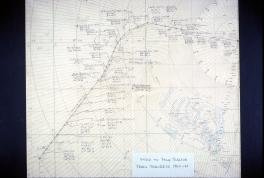

From November 1959 to November 1960, Henry worked at Byrd Station in West Antarctica with about 20 other people, a mix of research and support personnel. It was isolated, cold, and dark for about six months of the year, but Henry enjoyed it. For the first time in years, he was using his hands to do something useful and he loved it. He loved it so much that when the aurora job was nearly up, he started badgering every person he could to find an open spot on a crew to do field work in Antarctica. Unfortunately, most crews were selected months in advance and the odds were slim. As luck would have it, there was a United States Navy tractor train traveling from Byrd Station to Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, and there happened to be two extra cots on their rig. One of those spots went to a researcher from the University of Wisconsin, Forrest Dowling, and the other went to Henry. After securing the opportunity to do field work in Antarctica, all Henry needed was to figure out something to do while he tagged along.

The answer came in the form of Richard Goldthwait, a prominent glacial geologist working at the Byrd Station at the time, who told Henry that “if he was gonna take up a spot, he at least ought to do something useful.” The Navy’s route would go to the South Pole over the ice, moving through little-studied areas of the continent and making their team the first United States party to travel to the South Pole on the ground. As the founder and then director of the Institute of Polar Studies at The Ohio State University (later renamed the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center), Goldthwait had a special interest in this untouched snow. He taught Henry how to take glacial samples from a two-meter-deep pit in the ice and how to take pictures of the ice layers. If Henry found anything interesting in the ice, Goldthwait suggested that he should come to the Ohio State University and write a paper about it.

The Navy mission lasted from December 1960 to January 1961 and Henry did find interesting data along the way. After a brief stint back at Byrd Station to help construct an aurora observation substation, he returned to the United States, found Goldthwait in Ohio, and published a paper about his data in the Journal of Glaciology. Following the publication, Goldthwait offered Henry a position on his next crew to Antarctica which he declined. Instead, Henry went to live with a friend in Boulder, Colorado. This break didn’t last more than a few months before Henry reconsidered his decision. Ready for fieldwork, he called Goldthwait to ask about that mission. Although the team was full, Goldthwait advised Henry to return to Ohio State University and start a master’s degree while waiting for the next mission. With the possibility of more fieldwork on the horizon, Henry agreed.

During coursework for his degree, Henry spent most of the time studying ice alongside his fellow researchers in the field in Antarctica and other regions around the world. He graduated in 1966 with a master’s in geodetic science from The Ohio State University, earned a degree in photogrammetry in 1969 from ITC in Delft, Netherlands, and began pursuing a doctorate in geodetic science soon after. Although Henry had completed all the coursework, passed the general examination, and started the research, he never got around to the business of writing a dissertation. He was busy using his hands and traveling the world. He let the PhD go and instead settled for the designation “ABD” (All but Dissertation) in 1974.

In 1988, The Ohio State University announced a retirement incentive program for employees. By that point, Henry had accumulated 15 years of field work and been a staff member at the Byrd Center for 25 years. He qualified for the highest reward level for the program and, at 56 years old, it seemed like an offer too good to refuse.

Henry carries on volunteering, doing field work, and helping others with research at the Byrd Center. He completed his last field expedition with a 2011 trip to the Quelccaya Ice Cap in Peru at the age of 78. His numerous contributions have been honored through both an award and a scholarship named after him: the Henry Brecher Technical Achievement Award and Garry McKenzie & Henry Brecher Undergraduate Scholarship. He has also had several opportunities to discuss his adventures over the years, including this past September at the International Mountain Conference in Austria which is currently the largest mountain research conference in the world.

Over the course of 60 years, Henry has seen the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center change names, faces, and leadership many times, but he’s still going strong. Although much could be said about the man who’s faced so many challenges and touched every corner of the globe, perhaps Henry says it best: “It has been better than working for a living."

Learn more about Henry Brecher's career

"Ode For Henry" by Susan Schwartz Twiggs

“Henry Brecher: Byrd Station Antarctica 1959-1961” from the Byrd Polar YouTube channel. This video has also been cross posted onto Vimeo

“Interview of Henry H. Brecher by Raimund E. Goerler” from the Knowledge Bank at Ohio State University

“Studying the Aurora Australis from Antarctica” from the College of Education and Human Ecology at Ohio State University

Digital collection of Henry’s photographs from the University Libraries at Ohio State University

Updates:

7/2024: Remembering Henry Brecher

8/2024: Graz to Oswego by Henry Brecher, This seminar was given by Henry Brecher in Scott Hall on September 7, 2022

11/20/2024: Henry's celebration of life

12/11/24: From war refugee to polar pioneer: his brave journey, Ohio State Alumni Magazine