— HISTORY CORNER —

Frederick Cook Receives a Presidential Pardon

by Dr. Marissa Grunes

Dr. Marissa Grunes, Lecturer in the Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics & Society at the University of Colorado Boulder, is the recipient of the 2025–2026 Byrd Center’s Polar Archives Research Award. Recognized for her exceptional scholarship, Dr. Grunes began her research fellowship on June 23, 2025. During her tenure, she will utilize the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center’s unique archival collections to further knowledge of polar history and exploration.

Who first reached the North Pole? Is 14 years too long a prison sentence for defrauding investors? Too short a sentence?

These questions came up on my first day at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archives at The Ohio State University.

What’s investment fraud got to do with Antarctica? you ask.

Today we venture into the collections of a half-forgotten polar explorer: the American Frederick A. Cook.

Half-forgotten now, perhaps, but his was a big name in the 1910s and 1920s. Those were the days when being a polar explorer could earn you a ticker-tape parade in downtown New York City and a meeting with the President of the United States…but for Cook, it meant a presidential pardon.

The Collections of the Frederick A. Cook Society: Polar exploration and…defrauding investors?

First expedition to reach the North Pole! Or was it?

In April 1909, the American explorer Robert Peary allegedly set foot at the North Pole, arriving an hour after his companion, Matthew Henson, had scouted on ahead. Upon getting home, they heard that Frederick A. Cook had also just returned from the Arctic…and he claimed he got to the North Pole a year earlier, in April 1908.

Cook led one of the most storied (and colorful) careers in polar history. He was one of a small handful of humans who had spent winters within both the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, and he counted as one of his dearest friends the monarch of polar exploration, Norwegian Roald Amundsen. Cook and Amundsen had been among the first men to survive an Antarctic winter, and Cook’s role as ship’s doctor had cemented his place in Amundsen’s good books.

Back from the North Pole (maybe), Cook explained that he had once again been forced to survive a polar winter, this time almost starving to death in Greenland. He had been gone 14 months.

Peary turned out to be a bitter opponent. He and his supporters began a campaign to discredit Cook—not a hard thing to do, as Cook had already apparently lied about being the first to summit Denali. Cook had no record of arriving at the North Pole: he claimed he’d left his expedition documents in Greenland, but when a friend tried to bring Cook’s belongings home on Peary’s ship, Peary refused to carry them. The boxes stayed in Greenland and have never been recovered.

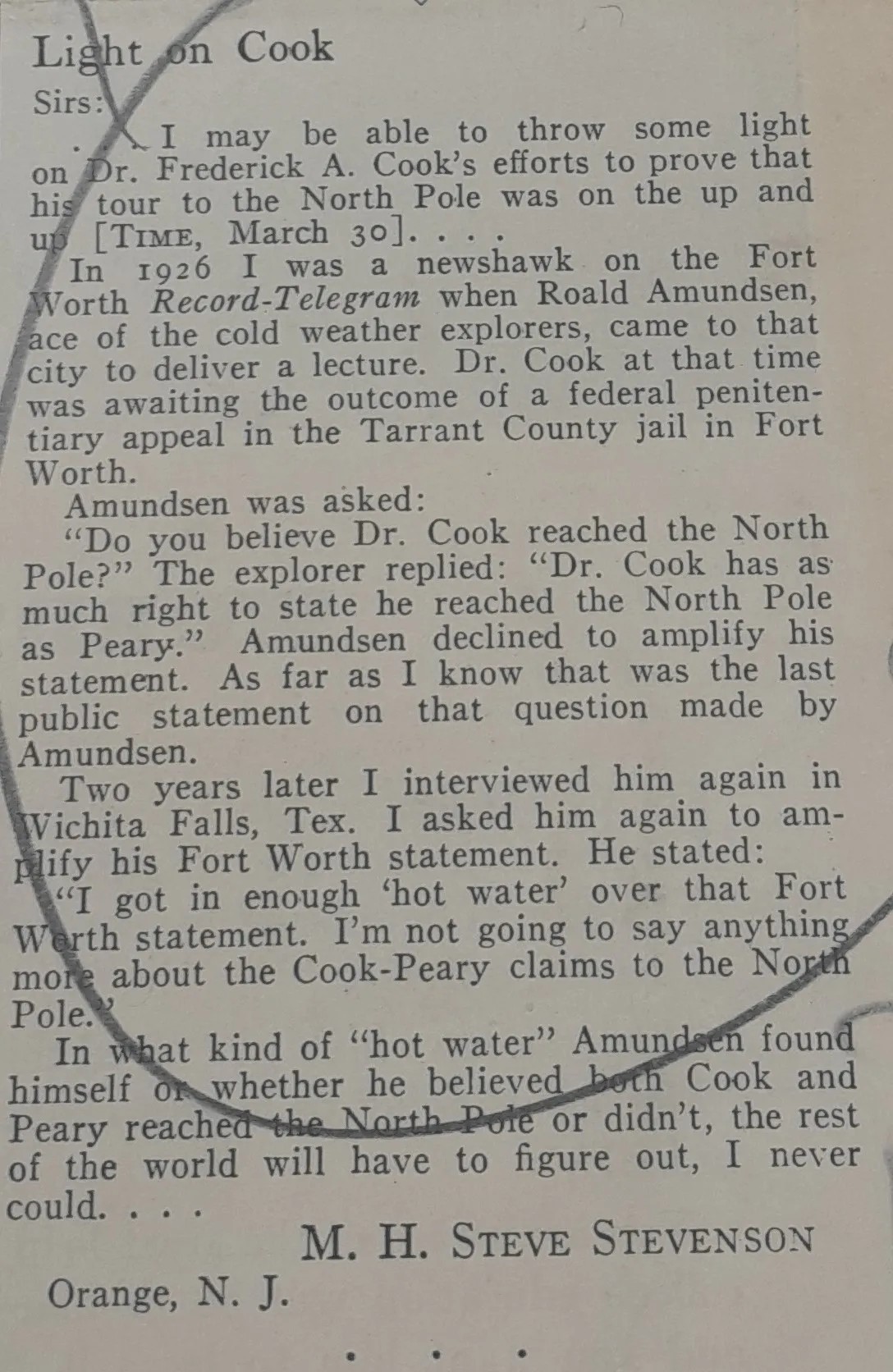

Was Peary’s ruthless campaign itself a coverup? Many people apparently thought so. Among them was Cook’s old shipmate Amundsen. In a newspaper clipping held in the Byrd Polar Archives, he’s quoted as saying: “Dr. Cook has as much right to state he reached the North Pole as Peary.”

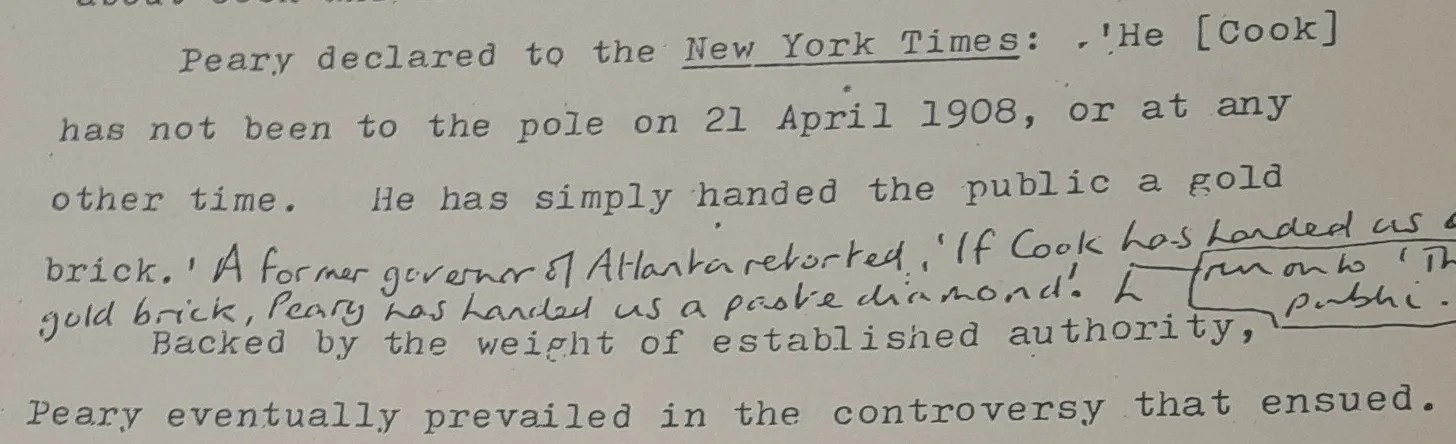

Another newspaper clipping from the collection has an even juicier remark. Responding to Peary’s accusation that Cook had “simply handed the public a gold brick,” someone has written: “A former governor of Atlanta retorted, ‘If Cook has handed us a gold brick, Peary has handed us a paste diamond.’”

Cook ended up being sentenced to 14 years in prison for a scheme to defraud investors based on fake oil and gas leases in Texas. Some thought his sentence too harsh, while the judge who imposed it remarked decades later that “if he got everything that was coming to him for all the things he has done, he ought to stay in the Penitentiary for life.”

Cook’s daughter Helene Vetter worked for decades to research the accusations against her father and clear his name. The collections at OSU are in part the fruits of her labors (including the handwritten note in the clipping above, though that may not be her own handwriting).

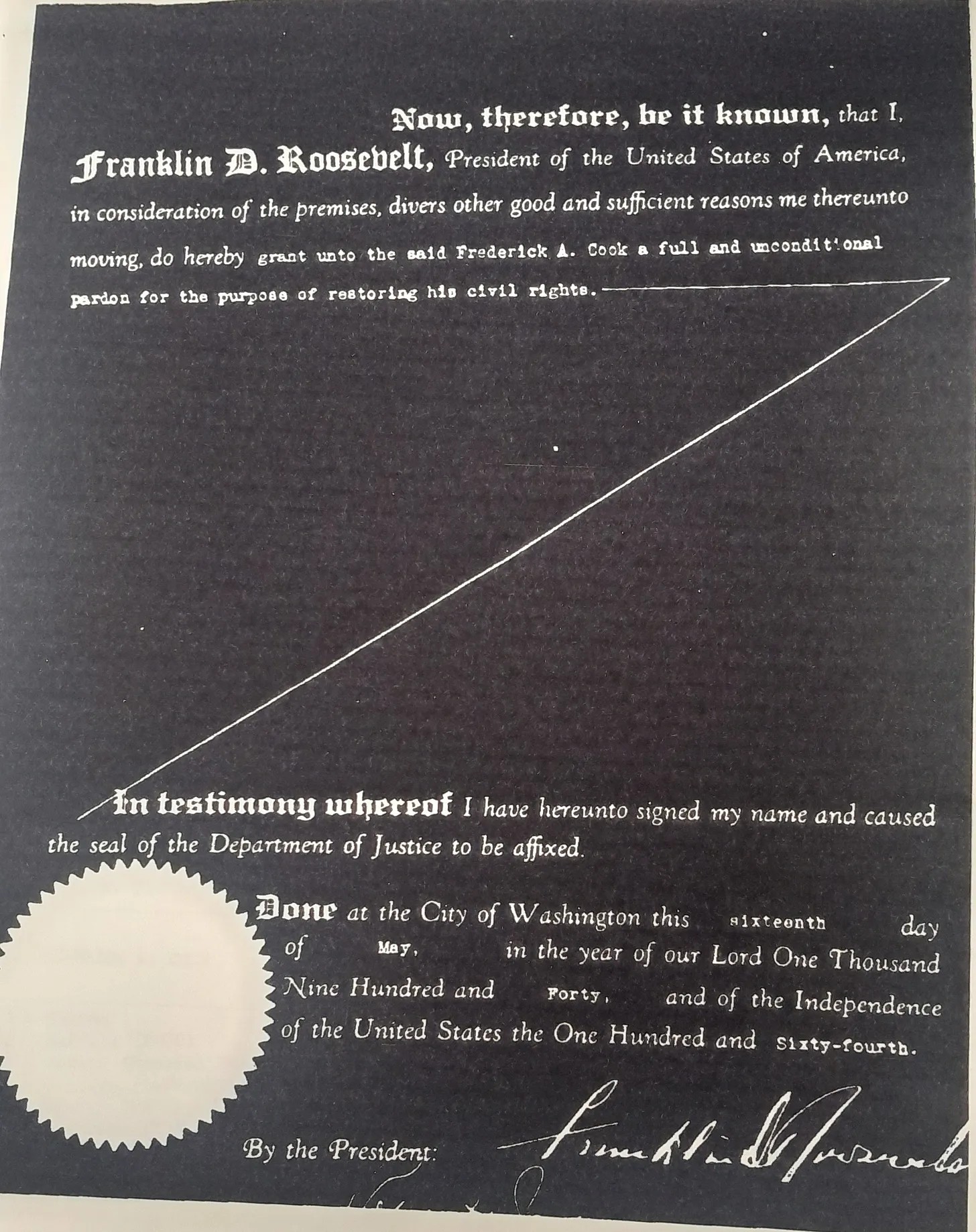

Cook’s claims remain in doubt, but his civil rights were restored in 1940 with a presidential pardon from FDR.

Being a famous explorer may not have helped Cook get his pardon, but it may not have hurt. FDR’s secretary, responding to the request for a pardon, called it “a corking good human interest story.”

So, who actually reached the North Pole first? In fact, it might have been the man who was also first to the South Pole: none other than Cook’s old friend Roald Amundsen. Amundsen and his crew floated over the Pole in an airship on May 12, 1926. They arrived a few days after Admiral Byrd supposedly made the flight, but Byrd’s claims have been questioned, too. Amundsen’s flight was a different kind of first: the first trip to the North Pole not shadowed by controversy.

Learn more about Dr. Marissa Grunes' Gone Incognita Blog and Subscribe.

She can also be reached at marissa.grunes@colorado.edu.