— HISTORY CORNER —

The British Imperial Antarctic Expedition that never was

by Dr. Marissa Grunes

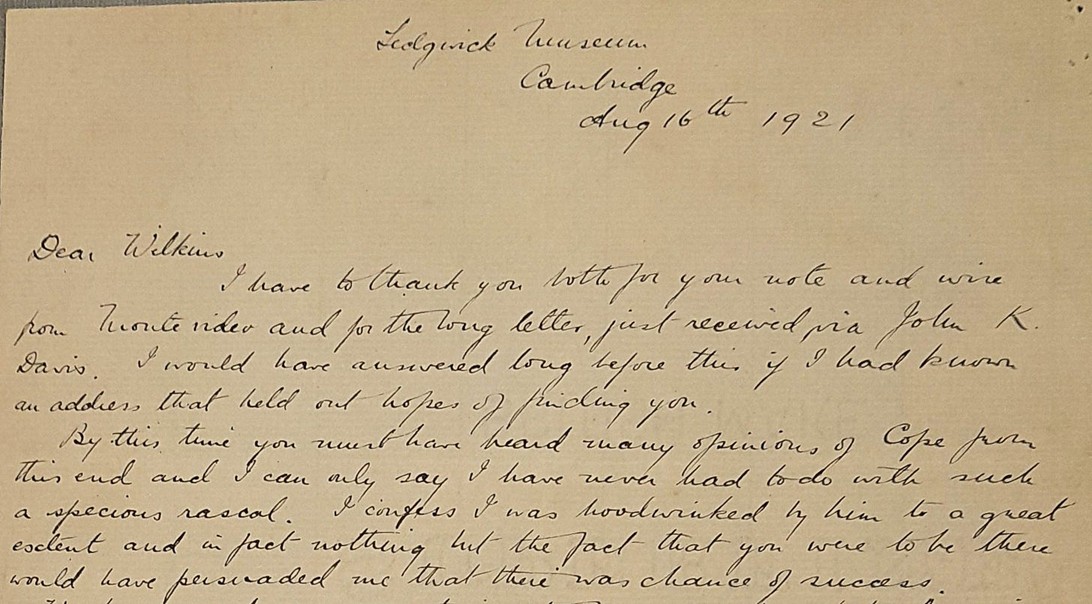

“By this time you must have heard many opinions of Cope from this end and I can only say I have never had to do with such a specious rascal.”

George Hubert Wilkins had a problem…and it was an unexpected problem, too: people trusted him.

It was August of 1921 and the sun was returning to the Antarctic. It would shine with equal grace on the ice and sea and penguins and on two young men—or on their lifeless bodies. No one could say.

These two young men had been left alone on the Antarctic Peninsula over the winter. There, they were to take scientific observations and wait for summer and the return of their expedition leader.

But their leader wasn’t coming back.

Maxime Charles Lester was the elder of the two, a wizened 30 years old. The other, Thomas Wyatt Bagshawe, had quit school to join the expedition at 19. He was now a full 20 years old—and while boys younger than he had fought in the trenches not many years before, his father was still worried.

Keen to make their mark, Lester and Bagshawe had gotten caught up in one of the strangest (and smallest) Antarctic expeditions of all time. Now they were stranded in Antarctica, and Mr. Bagshawe expected Wilkins to do something about it.

Commander of the British Imperial Antarctic Expedition

It sounded official enough. The British Imperial Antarctic Expedition was to be a massive endeavor, involving some 50 people, 2 airplanes, multiple ships, and several years of Antarctic exploration along the Peninsula. Its Commander, John Lachlan Cope, had been South under Shackleton. If there was ever a name to depend on in dire trouble, it was that of Shackleton.

On paper—specifically, papers held at the Archives of the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center—the B.I.A.E. looks impressive. Page after page lists detailed requests for the best technology, from navigational theodolites and telescopes for geodesy, to electric anemometers and 1000 balloons for meteorological study. Most exciting for George Hubert Wilkins, a budding pilot, were the airplanes. Two planes, with two pilots and three mechanics, were expected to join the expedition. One was to be a Blackburn Tractor Biplane, designed by the same company that supplied the British Royal Air Force. Only the best for John Lachlan Cope, Commander, B.I.A.E. The proposed budget is listed as £150,000.

In retrospect, there were perhaps signs that something was amiss. For one thing, Cope, a 27-year-old graduate of Cambridge with a habit of inviting himself over to people’s houses and drinking their whiskey without permission, didn’t seem to sign his actual name to anything. Cope had been South on the Endurance expedition, true, but he had been on the support party, across the continent from the Boss, so he never even saw Shackleton during the expedition.

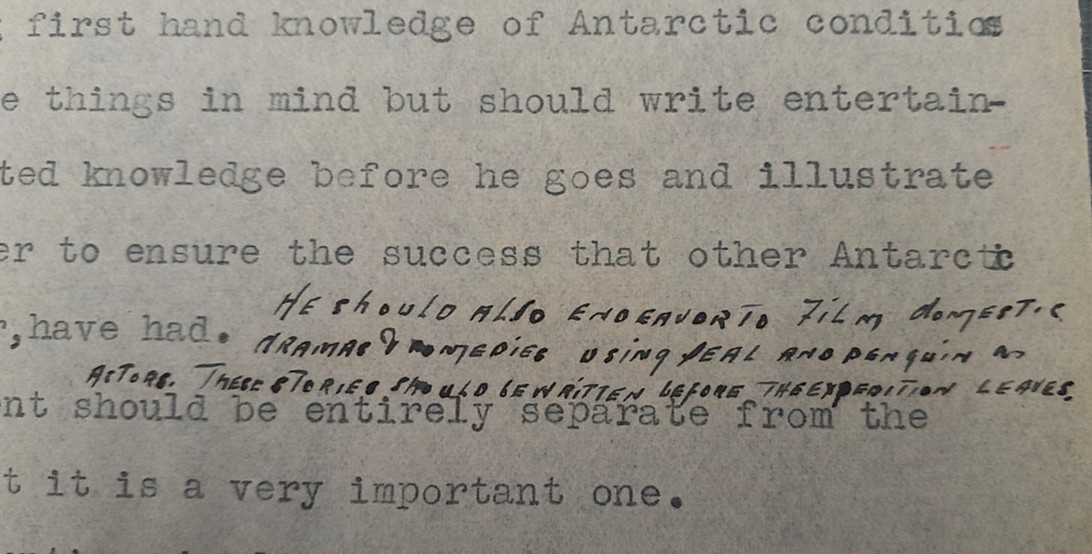

Other hints of trouble are more amusing. A personal favorite of mine appears in instructions for the expedition’s photographer. Here, Wilkins himself has handwritten an idea that must have thundered out of the sky like a bolt of genius: “He [the photographer] should also endeavor to film domestic dramas & comedies using seal and penguin as actors. These stories should be written before the expedition leaves.” One wonders what gave rise to that suggestion.

As the plans and planes multiplied, Wilkins saw history in the making: “I was second in command….I had 12 airplanes and was going to fly to the South Pole and abandon them on the way, filling up the other machines as we abandoned one, and leave them all behind.” This was a staged launch vehicle on overdrive.

Wilkins might as well have flown to the Moon.

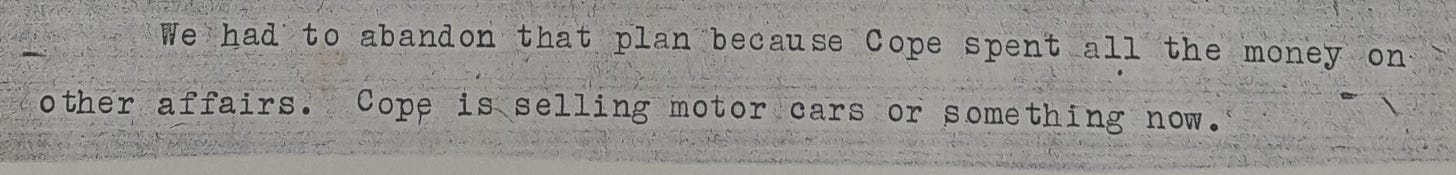

“We had to abandon that plan,” Wilkins continues, “because Cope spent all the money on other affairs. Cope is selling motor cars or something now.”

Whether there ever was a B.I.A.E. is questionable. Wilkins arrived in South America to find Cope and two young men—Lester and Bagshawe—preparing to thumb a ride on a whaling vessel. They were to spend a winter on the Peninsula and then catch a ride back in the spring.

A few weeks after arriving, Cope left. He needed to go to London, he said, to get money for a ship. Wilkins was no fool. He left too, and—according to his account—tried to persuade Lester and Bagshawe to do the same. He wrote: “Both were very fine and anxious to do all they possibly could.”

Lester and Bagshawe stayed, camping in an abandoned boat at what became known as Waterboat Point. Wilkins later discovered that Cope had threatened the manager of a whaling station, forbidding any whalers from picking the boys up before winter. Cope thought he could raise more money with men still in the Antarctic.

Of course Cope did no such thing. Which left Wilkins with that funny problem: people trusted him. Wilkins was arrested at the British Falkland Islands for abandoning the boys, and held responsible because—well, because he was the only responsible sort of man there. He writes: “It appears that the father of one of the boys [Bagshawe] had agreed with Cope if I would take full responsibility….I had never heard of this until we were in the Falklands. The Governor held me responsible, as did the Royal Geographical Society and the boy’s father.”

Bagshawe senior was a powerful industrialist and not a man to take the disappearance of his son sitting down. He got ahold of Frank Debenham, a veteran explorer who had traveled to Antarctica on Scott’s fatal Terra Nova expedition ten years earlier. Debenham was worried too:

“To stay down for a winter there is nothing to men with age & experience,” he wrote from firsthand knowledge. “But two youngsters like that, full of zeal, may very easily make a hopeless mess of things….I don’t wish to be an alarmist but of course if they are not picked up, (or if they have got themselves into trouble or tragedy) there will be a most unholy row, and the Admiralty, R.G.S. and other bodies will take a hand.”

Wilkins had to get the boys out. Of Cope, Debenham wrote: “I can only say I have never had to do with such a specious rascal.”

As a matter of fact, the two young men were fine. They had such a great time that they insisted on staying through the summer. They returned home on a whaler in January 1922, not much worse for wear.

Wilkins was surprisingly gracious about Cope in his later account. “At heart, Cope wasn't half bad,” Wilkins wrote. “He was foolish in many things and did not mean any offence.”

Perhaps people were right to trust Wilkins. His psychological insight seems astute, at any rate. When the young men asked to stay, he spent some time observing them, watching them get into fights and figure things out.

“Had they been boon companions without any trouble, I would not have let them stay,” Wilkins later wrote. “But any two men who can have a row in the morning and get over it in the afternoon, can get along anywhere.”