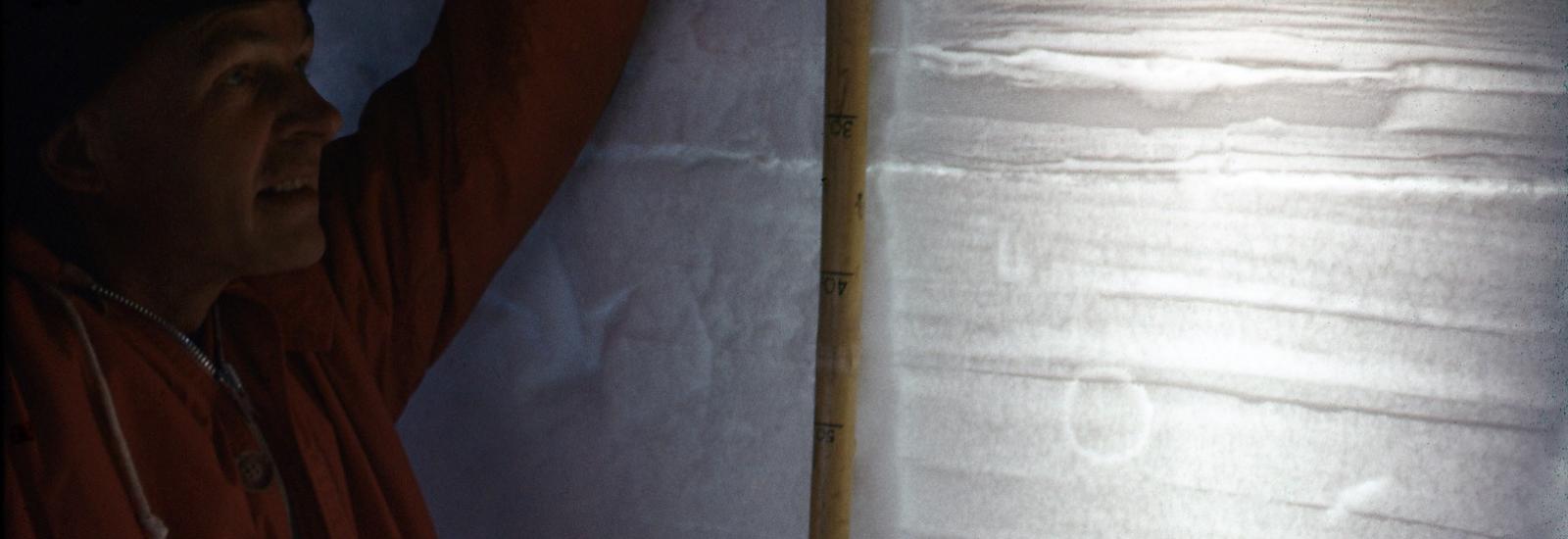

Richard Goldthwait in snow pit at Byrd Station to show Henry Brecher how to make standard traverse snow pit measurements, December 1960. Image by Henry Brecher.

— HISTORY CORNER —

Trailblazer of the Ice

Richard P. Goldthwait's Life, Legacy, and the Formation of The Byrd Polar Research Center

by Louisa Kaplan

Fondly called Doc G, Richard P. Goldthwait was one of the founders and first director of the Institute of Polar Studies at The Ohio State University, now known as the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center. Founded in 1960, Goldthwait served as Director for five years, cultivating the emerging center into the hub of polar research and outreach that it is today.

Richard Goldthwait was born June 6, 1911, in Hanover, New Hampshire. His father James was a geology professor at nearby Dartmouth College. James was an avid outdoorsman and skier, and he started teaching Richard to ski from the age of three. As the young Goldthwait got older he began helping his father with geology projects, and eventually decided to pursue the subject himself. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1933 with a B.S. in geology and recognition from the honor society Phi Beta Kappa. In 1934, he went to Alaska and was one of the first to use seismic surveys to study glaciers. Goldthwait went on to attend Harvard University and complete an M.A. in 1937, and a Ph.D. just two years later in 1939. After that, he worked as an instructor first at Dartmouth, and then at Brown University before becoming an associate professor at Ohio State in 1946. During World War II, Goldthwait was a civilian technical representative for the Army Air Force and received an Award of Distinguished Merit for his service.

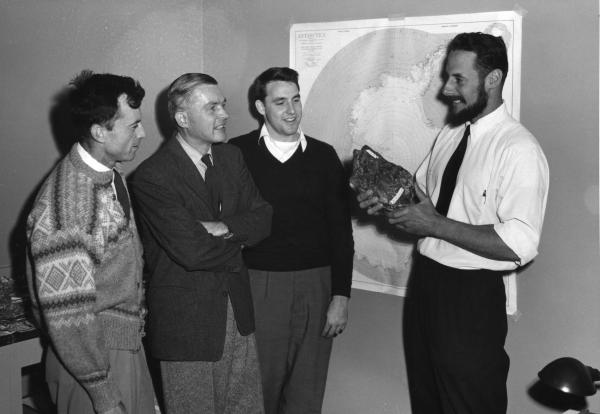

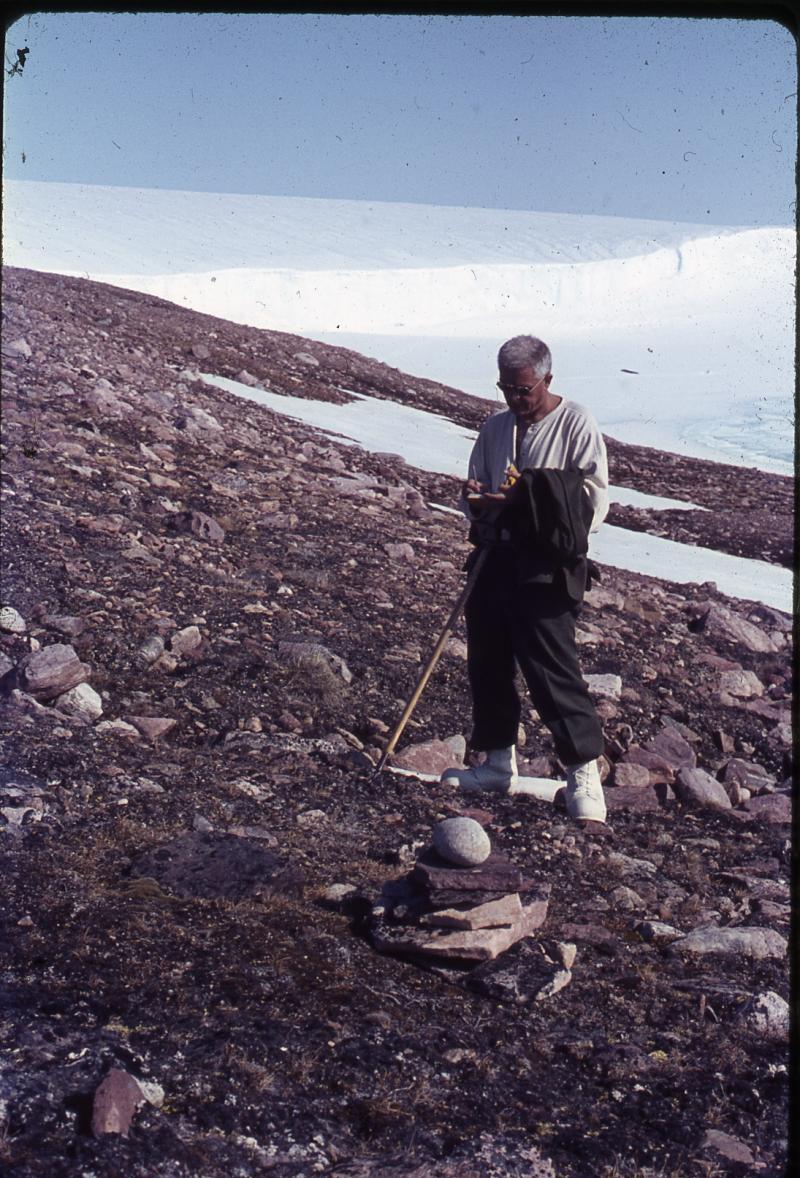

Over the next 15 years, he would participate in numerous expeditions to study glaciology, including to New Zealand and Antarctica. Dr. Goldthwait’s specialty was Quaternary geology (covering 2.58 million years ago to present), specifically glacial geology. He was following directly in his father’s footsteps, and in 1951, Goldthwait and his father partnered to write and publish a book on surficial geology (see sources, item 3). One unique expedition on Goldthwait’s resume was the Reynolds-Boston Museum expedition of 1948. Goldthwait went as a geologist to study Mount Amne Machin, a colossal peak in China. However, the ostensibly scientific expedition was actually an elaborate and poorly planned stunt by an American entrepreneur trying to sell ballpoint pens, which had just recently come on the market in the U.S. The trip was full of incidents and ended in a daring escape from Chinese authorities 4. The rest of his expeditions were presumably more orderly, and much more productive scientifically. In those 15 years, Goldthwait published dozens of scientific papers on glacial geology, frequently involving the ice ages in New Hampshire and Ohio. In 1953, the military asked him to lead a 15-man research group in Greenland. He continued this research in later years under the Army Corps of Engineers and brought Ohio State graduate students and faculty along on field expeditions. By 1958 Goldthwait was president of the Ohio Academy of Science, a member of several national scientific organizations and committees, and had achieved a myriad of other feats in the field of geology that are too numerous to list here.

It might be argued that Goldthwait’s most influential and enduring contribution, however, was his involvement in the formation of the Institute of Polar Studies at The Ohio State University. Founded in 1960, the Institute’s primary mission was to cultivate and advance polar research. Funded by Ohio State and outside federal agencies, the Institute’s early research programs included geology, glaciology, climatology, and meteorology. Researchers from the Institute conducted research in Antarctica, the Andes, China, Greenland, and Alaska. Dr. Goldthwait served as Director of the Institute for the first five years, orchestrating polar and alpine research expeditions all over the world. He was also able to bring students and scientists to the Institute via Teaching and Research Assistantships. His contributions to glacial geology earned him recognition as one of the “Ten Outstanding Men of the Year” in Columbus in 1962, and a Congressional Antarctica Medal in 1968.

In the early 1980s, there were murmurs that the Byrd estate was looking for a home for the late Admiral Byrd’s collection of documents. This was big news, as the estate had been in a legal tangle since Mrs. Byrd’s death in 1974. There were two major players vying for possession of Admiral Byrd’s papers: The Ohio State University, and Dartmouth College. At this point Dr. Goldthwait was in his 70s, and he and his wife Kay were living on the peaceful island of Anna Maria, Florida. He was the Professor and Director Emeritus of the Institute, and he had not had anything to do with Ohio State’s or Dartmouth’s proposals for acquiring the Byrd papers. When colleagues started requesting his advice on where the papers should go, he was caught between his hometown school and alma mater, and the Institute that he helped found. In a letter to the executor of Mrs. Byrd’s will, Goldthwait sided with Ohio State. He wrote that although Dartmouth was very prestigious and could do an excellent job preserving the documents, Ohio State was a livelier and more vigorous hub of polar research. Goldthwait felt the papers would be used extensively there by scientists at all levels and from all over the world. OSU also proposed to change the name of the Institute to the Byrd Polar Research Center, as a permanent commemoration to Admiral Byrd. All of these factors, including Doc G’s endorsement, held weight with the Byrd family. The papers were purchased by The Ohio State University, forming the nucleus of what would become the Polar Archival Program.

Dr. Goldthwait was an active scientist for the rest of his life. Even after moving to Anna Maria, he would sometimes travel to Ohio State to work in his office, and he continued to lead groups of graduate students on trips to study glaciology. Dr. Goldthwait died suddenly at the age of 81 on June 7, 1992, from a cerebral hemorrhage he suffered while collecting water samples with his brother in New Hampshire. The Goldthwait Polar Library at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center is named for him, as is Mt. Goldthwait in interior Antarctica . Richard Goldthwait was an extremely respected Quaternary and glacial geologist, and he was admired greatly by his family, his colleagues, and the dozens of graduate students that he guided.

Images were provided by Henry Brecher and the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program. Visit the Polar archives to learn more.

Sources:

- The Ohio State University Archives, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, UA.1993.0093.0001, Faculty Papers, Richard Parker Goldthwait

- “Memorial to Richard Parker Goldthwait 1911-1992.” Department of Geological Sciences. University of Washington. Accessed February 5, 2024. https://rock.geosociety.org/net/documents/gsa/memorials/v24/Goldthwait-RP.pdf

- Goldthwait, J.W., Goldthwait, L. and Goldthwait, R.P. (1951) The geology of New Hampshire. Concord, New Hampshire: Dept. of Resources and Economic Development.

- Chen, Shiwei. “The Making of a Dream: The Sino-American Expedition to Mount Amne Machin in 1948.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 37, no. 3, 2003, pp. 709–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3876615. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.