By Kat Cartwright

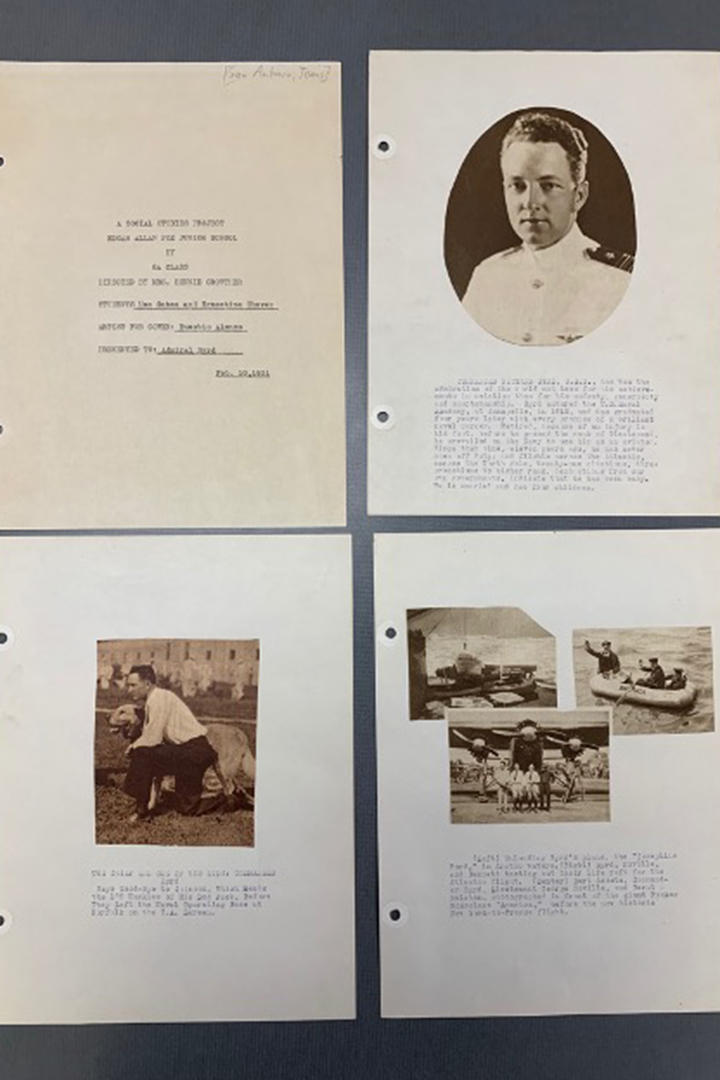

Schoolchildren across the U.S. eagerly tracked the travels of explorer Richard E. Byrd throughout the interwar years. During his flight to the North Pole in 1926, transatlantic flight in 1927, and three expeditions to the South Pole from 1928 to 1941, they read about his travels in the daily press, listened to his broadcasts on the radio, and watched him on the screen at the cinema. They also wrote thousands of letters to him as part of their schoolwork.

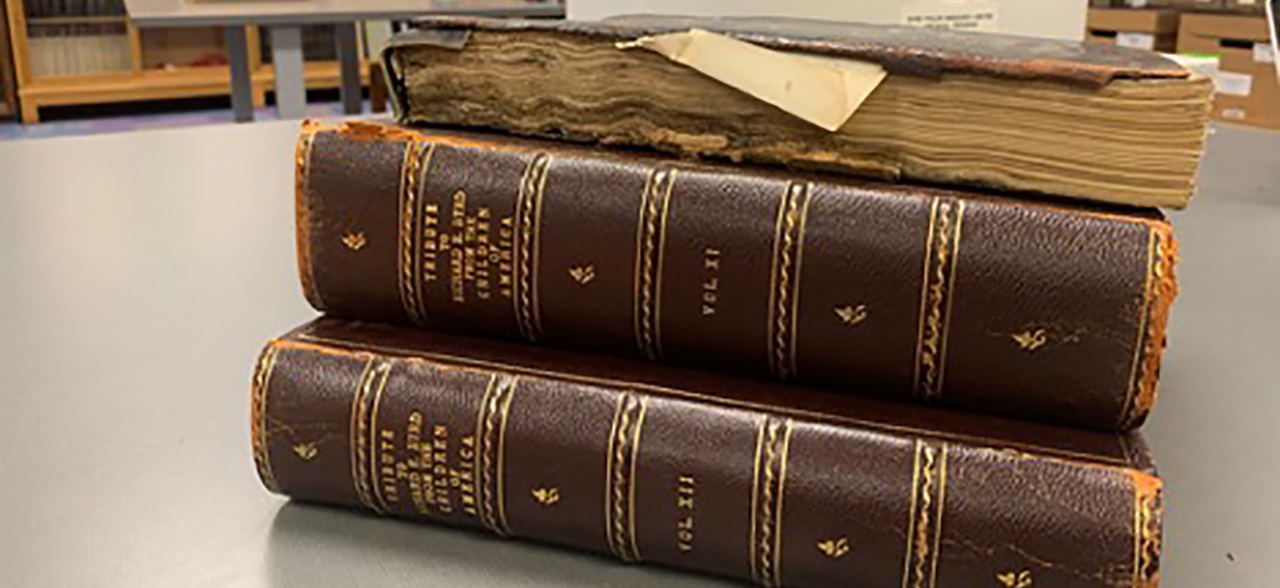

With a generous fellowship from the Polar Archives, I was able to look through these letters this past spring. Archival acquisition and organization tend to privilege the voices of adults, so the sheer number of schoolchildren’s letters was an exciting find for a historian of children and youth like myself. In my dissertation, I seek to prioritize students’ primary sources—such as artwork, letters and school assignments—and can often sift through hundreds of pages just to find one student’s creation during a day at the archive. Needless to say, my week at the Polar Archives was one of my most exhilarating archival visits to date.

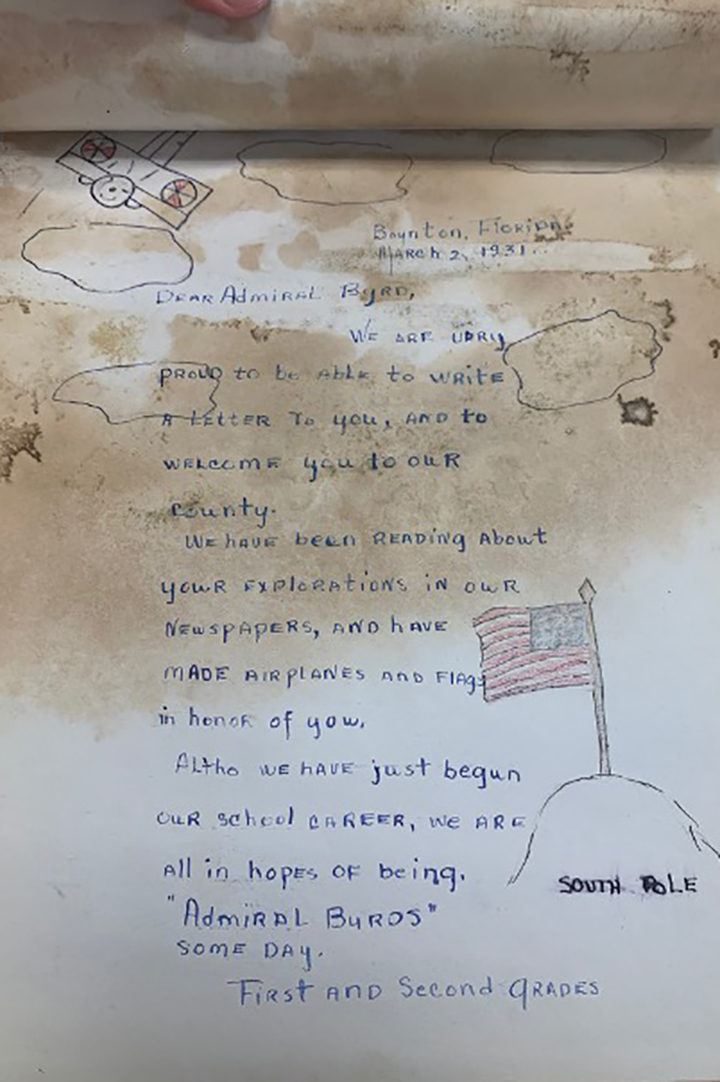

Looking through the letters, I learned that teachers used Byrd’s travels to enhance students’ schoolwork in nearly every subject. In history, teachers placed Byrd at the end of a long line of explorers, while in civics they encouraged students to see Byrd’s courage and bravery as traits that every American citizen should demonstrate. Students also used Byrd’s records of wind speed and direction for lessons in math and science and frequently created their own maps of Byrd’s expeditions in order to learn geography. Some students even joked that Byrd was creating more schoolwork for them, such as one student who told Byrd: “Though your trip has added another chapter for us to study in geography and history, I enjoy studying about it.”[1]

In addition to writing about how they were studying Byrd in their classrooms, students used their letters to express their likes and dislikes, as well as their future aspirations. For example, students frequently stated their plans to become explorers, scientists and aviators. One schoolboy in California declared in his letter: “When I grow up I would like to be a great explorer like you. I am eleven years old and when I am old enough I am going to try to go to places where no one has ever been before.”[2] A schoolgirl in Connecticut also wrote, “I hope some day to be a pilot myself. I am very much interested in both the Arctic and Antarctic Zones.”[3] This girls’ letter—as well as hundreds like it—suggest that many girls did not see their gender as something that could preclude them from following in the explorer’s footsteps, despite the fact that the gender norms of the period typed Byrd’s pursuits as masculine. As this handful of excerpts and accompanying photos indicate, these letters offer a valuable window into interwar teaching pedagogies, as well as the thoughts and dreams of students growing up in the interwar years.

Kat Cartwright is a PhD candidate at the College of William & Mary currently completing her dissertation on the history of global citizenship education in the U.S. between the world wars. Her research for this article was supported by the Polar Archives Research Award.

Footnotes

[1] Bernice B., Lynwood, California, National Education Association Tribute, Vol. XII, February 23, 1931, folder 3487, box 76.

[2] Bill J., Palos Verdes Estates, California, National Education Association Tribute, Vol. XII, February 23, 1931, folder 3487, box 76.

[3] Mary V., Hartford, Connecticut, National Education Association Tribute, Vol. XII, February 23, 1931, folder 3487, box 76.